As I describe it, this newsletter is an occasional guide to the news, politics, and culture of India. This assumes that I am—through my experience, temperament, passion, and skills—qualified to be a guide.

Without going too much into that question of qualification, let me just acknowledge that despite being Indian and being curious, I have significant gaps in my understanding of matters outside my core competence. That is why I don’t think of myself as an expert. In these pieces, I adopt the persona of a fellow traveller.

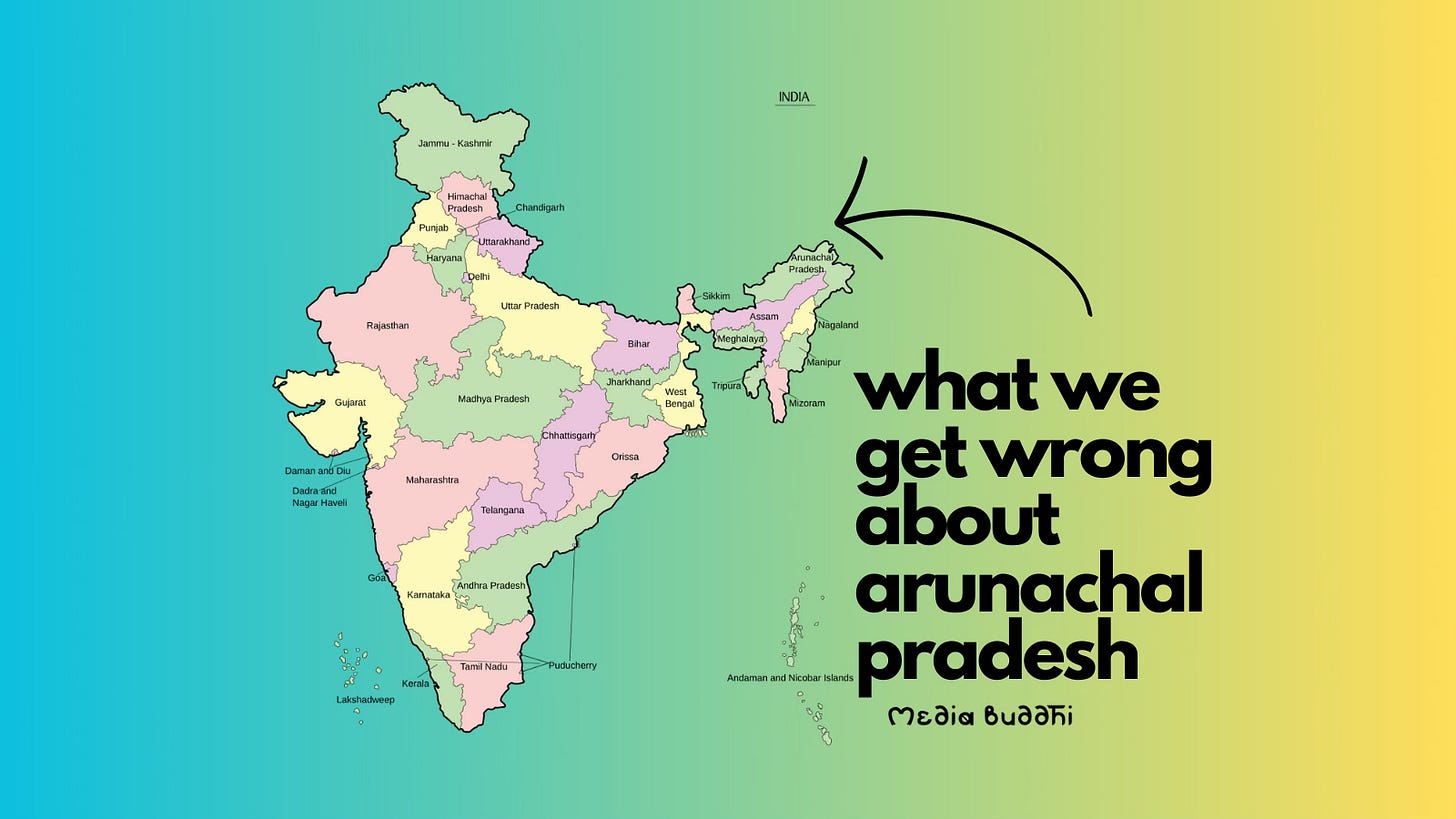

Probably the biggest gap in my understanding of India can be seen in the eight states that make up the Northeast, which are: Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura. [They were once known as the ‘seven sisters’ but Sikkim has since been added to the list.]

A year ago, during the uneasy calm after the violence in Manipur, we realised at work that even verifying basic facts in the state was proving to be very, very difficult. Not only did we—experienced journalists and fact-checkers—not seem to have a basic understanding of issues and tensions in the state, we simply did not know any people beyond the usual few that one goes to for a quick quote.

We decided to fill this void by creating a North-East Facts Network, or NEFN. This is the page we built to announce the project (link here).

Like all projects, this too has evolved since our beginnings in November last. Since February 2024, it has been led by Dr. Sabina Yasmin Rahman, an indigenous Assamese scholar with a PhD in Sociology from Jawaharlal Nehru University. The project has multiple moving parts, and it isn’t my intention in this post to describe what we’re doing in detail.

The term ‘mainland’ to describe the country minus the northeast is wrong, because one can drive to the northeast without leaving Indian soil. And technically, it is the Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep that are outside the mainland. And yet, I have came across this term with reference to the northeast multiple times, and realised that it has weight because it speaks to a feeling of dislocation from the plains of northern India and the Deccan plateau.

For a few months now, I have been making notes about what we get wrong about each state in the northeast, and today I’m sharing my learnings about Arunachal Pradesh.

1. Arunachal Pradesh is so diverse that they had to import a link language

It turns out that the most commonly used language (known also as a link language) in the state is Hindi! But this is not the Standard Hindi that one might find in Northern India. Instead, it is what is known as Contact Hindi, and it comes with its own unique grammar and innovations.

Take for example the word ‘cousin’. Standard Hindi has no word for it.

But as Anvita Abbi and Maansi Sharma write:

Arunachalese Hindi has adopted the Hindi word naklī, “artificial” and extended its use for “cousin,” as in naklī bahan “artificial sister,” i.e. “female cousin,” or naklī bhāī “artificial brother,” i.e. “male cousin.”

The linguist Peggy Mohan refers to the language as ‘Hindi’ (in quotes). She writes, “What is being called ‘Hindi’ in the North-east and across the Kala Pani in the Andaman Islands does not look as though it started out as Hindi. It has no gender, no ergativity, its plurals are expressed by adding the word log…” So the term “on seeing the dog” becomes kutta ko dekh ke, instead of kutte ko dekh ke.

But why do the people of Arunachal Pradesh need Hindi? Don’t they have their own language? The challenge, it turns out, isn’t that they don’t have one. Rather, it is that there are too many of them.

Here are the names of just some of them: Nishi, Apatani, Adi, Ahing, Bangni, Bokar, Begun, Deori, Gallong, Hrusso, Karko, Khamba, Khampti, Komkar, Lisu, Memba, Milang, Minyong, Mishing, Idu Mishmi, Digaru Mishmi, Monpa, Na, Nocte, Padam, Pasi, Ramo, Sajalong, Sherdukpen, Shimong, Sulung, Tagin, Taroan, Tibetan, Wancho, Zakring, Tangsa, Singpho, Monpa, Miji and Aka.

That’s 41 languages! The writer and journalist Samrat Choudhury says: “In Arunachal Pradesh, a traveller going from one hill to the adjacent valley and on to the next hill, may find that the dominant tribe, language and culture have all changed.”

Dr Jumyir Basar, a scholar who studies tribal world-views says that in the state, “diversity is so much that people with just 500 numbers or 300 numbers form [a community.]”

In such a situation, one needs a link language, and here it is Hindi.

On 11 July 2024, we held the Arunachal Pradesh Roundtable. We did our best to get as representative a panel as possible, and managed to get eight scholars from the state.

It was one of these scholars who explained to me that Hindi is the link language of the state.

Arunachal Pradesh is notable for the extent to which Hindi serves as its lingua franca, though similar patterns exist in other parts of the Northeast.

However, this linguistic situation is not without its complexities. Dr. Tarun Mene, an anthropologist whose work spans the spectrum of tribal culture and society with an emphasis on investigating suicide acknowledged the sentiment of 'Hindi imposition'—a concern well articulated in the southern states of India.

(For those interested, here’s a 49-second video on what Arunachali Hindi sounds like.)

2. The patriotism/insurgency axis works differently in Arunachal Pradesh

Because the Chinese threat is ever-present, mainlanders often forget that Arunachal Pradesh actually has three international borders: Bhutan to the west, Myanmar to the south, and China to the north.

Perhaps it is this looming presence of China, but the state has not experienced sustained, armed, and violent movements against the Indian state. Samrat Choudhury, the author of Northeast India: A Political History, writes, "Alone among the hill states of Northeast India, Arunachal Pradesh has had no notable separatist insurgency seeking freedom from India—although insurgents from neighbouring states such as Nagaland and Assam have used Arunachal for hideouts and bases."

During our roundtable, Dr. Tarun Mene broadly echoed these sentiments. With a slightly different emphasis, he said, "Insurgency was there, it is there also, but it does not affect the state as a whole."

I hail from Bengaluru in southern India which has a secure coastline. This means (among other things) that my patriotism is rarely questioned. But if one if from a frontier state, the question of patriotism would be more central to one’s existence.

Professor Kesang Degi who works in the field of women's education and the education of tribal communities said, "People from the mainland feel that the Arunachalese are not patriotic. That they are more associated with China. But actually it's not like that. If you come to Arunachal, people greet each other with Jai Hind. I am from Tawang, bordering China. People greet each other with 'Jai Hind'. I can say that tribal people of Arunachal Pradesh are one of the most patriotic people in the country."

Ranju Dodam, a journalist and a writer who reports on issues of environment, governance, and culture acknowledged Degi’s point but also noted that there is a narrative to portray the Arunachalese as the "most patriotic people in the country."

Dr. Jumyir Basar offered additional context: "Arunachal does not feature in the Indian imagination. It's only when the Chinese government claims Arunachal that the government and the citizens wake up and say Arunachal belongs to India."

There is also a misconception that Arunachali people are Buddhist, said Dr. Razzeko Delley, a scholar whose recent work focuses on Idu Mishmi shamanic rituals. "Whenever Chinese claims [on India's territory in Arunachal Pradesh] come, many people look through that prism that probably we are Buddhist and having affinity with Tibet," he said at the roundtable. This notion, according to him, is false and can be weaponized by China. "People of Rajasthan, Punjab, and Gujarat have a shared history with the people of Pakistan, but for us, we Arunachalis, we never had that kind of shared history with China." Delley says that only four or five percent of the Buddhist tribe which had an affinity with Tibetan Buddhism used to pay a tribute to theocratic Tibet.

Professor Ashan Riddi, who specialises in the history of indigenous communities in the state pointed out that while the people of the region were never a part of China, they weren't part of the British Raj either. As Dr. Delley reminded us, it was the British that paid the tribes to not attack them.

Dr. Basar agreed. She said, "Arunachal's tribes were self-governed and autonomous."

3. The women of Arunachal continue to deal with patriarchy

"Actually it's not like that," said Professor Kesang Degi, challenging the mainland belief that the women of Arunachal Pradesh are privileged. "Our society is a patriarchal one, and many-a-time because of gender inequality in education, they don't understand the status of women."

The reality is stark. Kani Nada Maling, the President of Arunachal Pradesh Women’s Welfare Society who also serves as the legal advisor to the state government pointed to persistent practices such as polygamy, bride price, child marriage, and rampant domestic violence.

Dr. Jumyir Basar also highlighted cultural restrictions: "There are communities like the Idu Mishmi where women are forbidden from eating meat." She continued, "Different cultures have different practices. Sometimes they get it right. Most times they get it wrong."

The pervasiveness of gender-based violence is particularly troubling. As Professor Degi explained, "It's very common. Eve-teasing, emotional abuse, sexual abuse is very, very common. And many times they don't understand that they are being emotionally abused."

4. Stereotyping of Arunachal residents

When it comes to stereotyping people from the state, "the first problem is our facial differences," according to Professor Riddi. Another issue, he said, is that there is hardly anything about the state in various school curricula around the country.

"They call us chinkis. We are very sad when we go outside our states—they consider us as very cheap," said Kani Nada Maling. If not that slur, then there's the 'Chinese' or 'Nepali' identity that is imposed on the people of the state, said Dr. Tarun Mene.

"We have this misconception about the tribes. They have been exoticized," said Dr. Jumyir Basar. There's the wrong belief that tribal people "come from the forest, wearing leaves and all." Dr. Tarun Mene echoed this: "People think we live in the jungle, not in a house."

There is yet another misconception. As Dr. Mene explained, "People may think of Arunachal as a non-vegetarian state, so vegetarians may not visit."

5. Tribal communities in the state are not ‘Adivasis’

"Unlike the perception outside of the Northeast, the word 'tribe' doesn't necessarily have negative connotations for us. We are very proud to wear that tag, we are tribals," said Ranju Dodam.

While the term 'tribal' has colonial echoes, Dodam acknowledges its varied reception: positive within Arunachal, but often negative outside the Northeast, in tribal belts, and in corporate and academic worlds. "I don't have a problem with the word ‘tribal’," he said.

The distinction between 'tribal' and 'adivasi' is crucial here. Dr. Jumyir Basar explained that while 'adivasi' has become the accepted term for indigenous or tribal people of India, it does not necessarily apply to indigenous people from Arunachal Pradesh.

In fact, 'adivasi' refers to an entirely different community in the region, as Dodam clarified: "What's happened in the Northeast is that the term 'adivasi' is used by the hill tribes to refer to just the tea tribes of Assam—tea labourers who were brought in from present-day Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, basically the Gonds and the Mundas... brought by the British as tea garden labourers."

He concluded by saying he prefers the term 'indigenous'.

6. Caste is not a significant feature in Arunachal

In response to a question about caste during the Q&A, Professor Riddi said, "Arunachal Pradesh is a society where in some parts, caste system is there, but rigid caste system is not there." He concluded, "Of course a class system is there."

The Constitution (Eighty-third Amendment) Act, 2000 formally recognises this distinction: "The tribal society in Arunachal Pradesh is casteless where social equality among men and women has prevailed over centuries and ages. Since no Scheduled Castes exist in the State and the State of Arunachal Pradesh is singularly free from the caste system, it is proposed to insert a new clause (3A) in article 243M of the Constitution of India, to exempt the State of Arunachal Pradesh from the application of article 243D relating to the reservation of seats in Panchayats for the Scheduled Castes."

7. Indigenous faiths are not being preserved

Arunachal Pradesh's indigenous faiths are very much alive - but they face complex challenges in preservation. Dr Razzeko Delley, who has extensively documented the cultural practices of the Idu-Mishmi tribe, especially their shamanic traditions and rituals, offers unique insight into this reality.

"Our people have not studied our shamanic culture. Shamanic culture has not been documented," he notes, highlighting a fundamental challenge in preservation.

The situation is further complicated by external influences. Drawing from his personal experience in an RSS-affiliated school, Dr Delley explains: "Our religion is very much messed up because of two very powerful external forces. The first group were the Christians who freely converted our people, despite the fact that there was this anti-conversion law prevailing in this state. But they built churches and they built schools, hospitals in the foothills of Assam. And they, you know, blatantly and presently converted our people."

"Next came the Hindu missionary group, especially backed by the RSS. In the name of reviving our culture and reviving our tribe, they have missed a lot. They just cloned our religion. Indigenous religion today is very much full of distortion, full of assimilation."

While Dr Delley welcomes efforts to preserve traditions, he emphasizes authenticity: "If they really want to conserve our tradition, practices, they are very welcome. But don't make us their cheap copy. Don't distort our culture."

Corrections and disclaimers:

It is my policy to make corrections in case there are any factual errors. In the case of errors of judgement or interpretation however, do write to me and I will make a good faith attempt to make changes if I believe they are warranted, or explain a point of view. All corrections will be reflected below.

Here’s a summary of the roundtable and here’s the YouTube recording.

Via WhatsApp, Arun C shares (via a second cousin) some wonderfully detailed thoughts which deepened my understanding of some issues:

Arunachal Pradesh is very diverse, as cited by the author. While fairly wide ranging, the article has left out a few aspects.

1. Many portions of the Northeast have link languages from outside the group. In Nagaland, it is Nagamese, which is a pidgin form of Assamese. Nagamese is to Assamese roughly what Bombay Hindi or Hyderabad Hindi or Chennai "Urdu" is to UP Hindi/Urdu. It dispenses with many verb conjugations associated with gender, number and class but is still completely comprehensible to an Assamese. My feeling is that erudite Shudh Assamese may prove difficult for rural Nagas to understand although on our recent visit, our crew was entirely Assamese and they did not seem (to me) to have any trouble in getting themselves understood by even the most remote, forest dwelling Nagas.

In Manipur, the link language is Meiteilon so it is interesting that tribes that overlap the border, such as the Zeliangrong, use different link languages, although they can communicate with each other using their own language. Reminds me of the Konkanis and their scripts. Those from Maharashtra use Devanagari. Those from Goa use the Roman Alphabet with Portuguese pronunciation. Those from Karnataka use the Kannada script and those from Kerala use the Malayalam script. But they do intermarry and all can speak Konkani even though each version may be slightly influenced by its home state language: Marathi, Portuguese, Kannada, Malayalam. But a Kannada Konkani husband cannot write a letter to his Kerala Konkani wife, unless both write in say, English.

To revert, the Hindi in Arunachal Pradesh varies sharply in quality over region and age of the speaker. In some areas, like Idu Mishmi, we found the Hindi excellent. On asking, we were told that the GOI had arranged for teachers from UP and Bihar during the formative years, hence the excellent Hindi. But this comes at a price as Sheila and I discovered at the museum near Roing, where we came across a very attractive Idu Mishmi girl, who spoke excellent Hindi and English but not a word of Mishmi, despite having studied at schools in Roing. More importantly, she did not feel any sense of loss. She thought that learning Mishmi was a waste of time and served no useful purpose given that ALL Mishmi speak Hindi, as do the rest of Arunachal, while the rest of the world uses English.

The bit on religion in the article has been abridged. The original religions varied from Tibetan Buddhism, near the border with Tibet, Theravada Buddhism in the lower hills and plains. The Tai Khamti, Singpho are predominantly Theravada and a sizeable chunk of Tangsa also are (Eg. Bela Tikhak is herself a Tai Khamti Buddhist but was married to a Tangsa from the Tikhak clan, who was also a Buddhist). The rest followed tribal animist and shamanistic religions for the best part, till recently. One of these religions, followed by the Adi, Apa Tani and some other tribes ( not sure exactly which), is Donyi Polo. Donyi Polo literally means Sun Moon and it is a Pagan religion. Major inroads have meanwhile been made by Christian missionaries with at least one major tribe Nyishi (or Dafla), being majority Christian today. In an attempt to stem the conversions to Christianity, it appears that the BJP and RSS are trying to popularise Donyi Polo amongst the non Buddhist tribes. Also, if we are not careful, we may see communal riots erupting in the near future because of a number of explosive demands, such as the denial of Scheduled Tribe status to Christian converts and its provision only to adherents of local religions. There are many other strains on view now. One, that we saw in considerable evidence, was the open discrimination practised against non Arunachali tribals, such as the tea tribals, derisively called "Adivasis". Also demands in the Miao/Vijaynagar area for the expulsion of all "outsiders" even though some, like the Nepalese settled by the GOI, arrived at pretty much the same time as the Lissus did from adjoining Burma and China. If care is not exercised now, Arunachal could become a problem area in the future.

Insofar as the racism faced by the people of Arunachal are concerned, I have heard a lot about it but never really seen anything major happen in my presence.

In the boarding school where I studied, I recall four Arunachalis from different tribes (which I only discovered in Miao from Bela), namely Hage Lodor, many years my senior, who Bela told me was from the Apa Tani tribe, Modo Ango, also many years my senior, who Bela told me was probably from the Galo tribe, Wang Lin Lowang Dong, Supreme Chief of the Nocte Tribe and Khanwang Lowang Dong, a cousin of Wang Lin. Wang Lin was two years my senior and Khanwang was one year my junior. All four were excellent in sports, Hage Lodor and Modo Ango in long distance running, Wang Lin in javelin and Khanwang in soccer. As a result, all of them were well liked. All of them too were friendly, except Wang Lin to an extent, who was reserved, possibly weighed down by his status as Supreme Chief of his people.

In Delhi Univ too, in my time, I didn't see any open racism but I acknowledge that reportage of racism has become a lot more common in the past 20 or 30 years.

I see Arunachal at the crossroads today, with pulls and pressures pertaining to religion, tribal identity and some other factors beginning to rear their head. The one thing that does not seem to be a problem...... is Hindi!!!

Good information on the other AP. The NE just gets clumped together. Only today I realised there are 8 states, whereas we are still stuck with 7 in our heads. Even when counting we do not seem to notice. Strange how our brains work. Very interesting to learn about the link language.