To pass the Kumbalangi Test for healthy masculinity, a film should have a male character:

A) talking to another person

B) about any vulnerability

C) other than anger or victimhood.

It is modelled on the Bechdel Test.

Read the essay that follows for how I arrived at this formulation.

In the world of films, you will find characters who occasionally ‘break the fourth wall’ by turning to the camera and addressing us, the audience.

This happens in Deadpool and The Big Short in Hollywood, Enola Holmes on Netflix, and Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro and Thappad in Bollywood.

In the very last scene of Ghazab (1982), as Dharmendra and Rekha turn to each other for a kiss, the ghost-spirit of Munna (also played by Dharmendra) turns to the camera and addresses us coyly, “Kyon? Kya dekh rahe hain? Aage dekhna buri baat hain. Ab hum toh chalte hain. Aap log bhi jaayo. Namaste!”

(What are you looking at? It is bad to look on further. I’m leaving now, you all leave too. Namaste!)

Borrowing from this tradition, let me also ‘break the fourth wall’ and address three questions you might have right at the beginning.

One: who am I to propose a test for healthy masculinity in films?

The answer: someone who didn’t know his version of masculinity was unhealthy.

In my zindagi ka safar, I’ve enacted several cliches of maleness. Some examples I can bear to share: during a challenging assignment at Change.org where I spent a year, I couldn’t even think to tell my boss, “I know this is one of the things you hired me to do, but I don’t quite know how to crack this. Can we sit together and work it out?”

I didn’t even think that sharing a vulnerability was an option.

Earlier still, when on the desk at CNN-IBN, I behaved in an entitled and patronising manner with my female colleagues. At the time, they were unhappy with me and I didn’t have the tools to understand why.

In recent years however, I’ve tried to do better.

So I suppose the only thing that qualifies me to propose this test is that I thought of it, and looked around to see if anyone else has done the same. Apparently, no.

Two: what do I mean by ‘healthy’ masculinity?

The answer to that will take another essay, but to make a limited point, I think the term healthy masculinity is better than positive masculinity or toxic masculinity. This is a conscious choice because positive and toxic are easily contested terms depending on which side of the gender debate you’re on. But we can all agree (I think) that we men tend to find unhealthy ways to express ourselves.

Three: what is the Kumbalangi Test?

The name ‘Kumbalangi’ comes from Kumbalangi Nights, a Malayalam film released in 2019. Directed by Madhu C. Narayanan, from a screenplay written by Syam Pushkaran, this film captures the lives of four brothers who live together in a small island close to Kochi, Kerala. The events in the film unfold over several days as the brothers are each forced to confront a dilemma.

In essence, the Kumbalangi Test asks the question, do male characters in films openly admit to vulnerabilities?

(Read through sections 3 and 4 for the exact formulation of the test, or click here for a short 166-word version.)

I got the idea for a Kumbalangi Test from a much older test, the Bechdel Test.

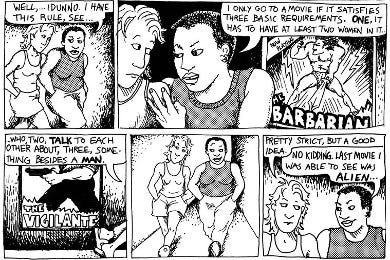

In order for a film to pass this test, it should fulfil the following three criteria:

(1) it has to have at least two women in it,

(2) who talk to each other, about

(3) something besides a man.

The test first appeared in 1985, in a comic strip by the American cartoonist Alison Bechdel and was named after her. Here’s the original cartoon, which was a part of Bechdel’s long-running series Dykes to Watch Out For:

Until I read about the Bechdel Test, I hadn’t realised that a bulk of films I had seen did not satisfy these requirements.

In the comic itself, the ‘rule’ is a satirical one, but because films consistently failed even this low bar, it became an unironic part of the culture.

On The Ladies Finger, an online women’s magazine where I first read about the concept, there are dozens of Bechdel tested reviews of films. Ditto with bechdeltest.com.

Here are some examples from them.

The Matrix Resurrections (2021) aces the Bechdel Test.

Don’t Look Up (2021) passes one out of the three questions in the Bechdel Test.

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) smashes the test.

Singham Returns (2014) fails the test.

Lucy (2014), despite having a female lead played by Scarlett Johansson, fails the test.

Queen (2013), led by the reliably controversial Kangana Ranaut, passes the test.

Bahubali (2015) fails the test. Vivekananda Nemana, writing in The Ladies Finger says, “the movie has four major female characters, all of whom are ostensibly strong…although it comes nowhere close to passing the Bechdel test. Two of them only interact once, for about five seconds, and that too about the hero…”

One might reasonably ask at this stage: iss mein kya hai bhai? What was the need for a Bechdel Test in the first place?

If films are mirrors of society, perhaps the opposite is also true: people can be influenced by the movies. Think of the following dialogues in films, and the values and frameworks they might have instilled in us:

Spiderman: “With great power, comes great responsibility.”

Value: One must not wield any kind of power without an understanding of the foreseen and unforeseen consequences of doing so.

Gully Boy (2019): “Apna time aayega.”

Value: Don’t give up hope even if nothing is going right for you right now.

Thappad (2020): “Yes, it’s just a slap, but nahi maar sakta!”

Value: One slap is better than ten slaps, yes, but even this just a slap violates my body and my sense of personhood.

Pink (2016): “No means no. And when someone says so, you stop.”

Value: Consent is all-important.

The point is, movies affect us, either by rousing our emotions or through gentle action. They influence our attitudes. The values that we then acquire as a result of this influence persuade us into behaving in certain ways.

The Bechdel Test became so important because it revealed to us several possibilities, one of them being: does our portrayal of women on screen reflect our attitudes and behaviour towards them in real life? The answer seemed to be: yes. This was also related to their numbers on screen. While women are roughly 50 percent of the population, they were not at all to be found on celluloid in proportion to their number and influence.

In a phone interview, Nisha Susan, a Bangalore-based writer and co-founder of The Ladies Finger, explains the importance of the Bechdel Test to me,

“There’s a well-established psychological phenomenon. If you put mostly men and a couple of women in a room and you ask someone, “are there a lot of women in this room?” People are likely to say, “yes, yes, there are a lot of women in this room.”

Nisha’s point is that in such cases, we might notice one or two women and assume, unconsciously, that there are a lot of women in the room.

The Bechdel Test works on the same level. One might think there are a lot of women in meaningful roles in a particular film. But when you actually take a look, you might realise that there are only one or two women in the film; and that these women are only there to serve or support the hero’s storyline.

Nisha continues:

“The Bechdel Test is not for sophistication, but for its simplicity. Because if you watch a film through a woman’s eyes, you might realise that ki oh shit ek toh there was only one woman, and all she did was lean against a wall and look sad. Or it might be that the only time a woman exists in a film is to serve some emotional arc for the man.”

Nisha’s point is a reminder of all those films where women are only there to play certain roles:

The mother or sister of the hero, who dies or is saved by him,

The love interest of the hero, who exists to be saved by him,

Or a vamp, whose terrible fate serves to provide a storyline for the hero.Suddenly the third requirement of the Bechdel Test, which is that a woman has to speak to another woman about anything other than a man, begins to make sense.

“There’s a phrase among people who write science-fiction and fantasy fiction,” says Nisha to me, “it’s about a woman who has been fridged. Being fridged means being a woman in fiction who exists only to die and in so doing, expand the emotional growth of the male lead. In which literally a woman exists for 10 minutes and she’s killed and she’s put in the fridge. Hence, fridged.”

The writer and musician Jayaprakash Satyamurthy adds some perspective:

“Fridging is a term comic book writer Gail Simone coined. It describes situations where a female character is maimed, injured or killed, purely to further a male character’s narrative arc. It came about when she used the example of a girlfriend of a Green Lantern who was murdered and found in a refrigerator. She then, together with other critics, put up a website called Women in Refrigerators which tracked this trope of female characters’ tragedies being used as a hook on which to peg male characters’ stories. And the term fridging became a popular pop-cultural shorthand for this phenomenon.”

Now that we have an idea of where I’m coming from, it’s also worth noting that the Bechdel Test is far from perfect, because you could have films that feature a hatred of women that nevertheless pass the test.

Goodfellas and American Pie 2 fall into this category.

Rather, it is a test that brings attention to the lack of representation of women in films. What this test, or the idea of fridging, does is help us understand that having cardboard cutouts instead of well-developed characters for women renders them invisible as surely as not having women characters at all.

Nisha and the other editors at The Ladies Finger stopped reviewing films using the Bechdel Test as a lens a few years after they began. The exercise had served its purpose. It was time to move on.

“In the beginning, it was for us a fun, rhetorical device”, she says, “we moved on because we felt like our reading population also had moved on. They’d got the point. So now when you look at film writing, even basic film writing in India, people write about representation comfortably. It’s not considered something only for academia.”

Which leads us to the question at hand: shouldn’t we have a test that performs a similar service for masculinity in films?

And if we do, should such a test be named for a Malayalam film in a film industry in India that is both uniquely progressive and notorious for its misogyny?

Kumbalangi Nights is about four brothers who hail from a fishing family: Saji, Bonny, Bobby, and Frankie.

Saji, the eldest, is a fisherman but he mostly lives off the wages of his friend, a Tamil-speaking migrant.

Bonny, the second eldest, is hearing and speech impaired. He prefers the company of his friends to his chaotic family. We are not told what he does for a living.

Bobby, the third brother, is a curly-haired, dimple-cheeked young man in his early 20s. He too, like his other brothers, is not yet invested with the idea that one must have a job.

Frankie, the youngest, is just a boy. He is at school on a scholarship but the film begins with him returning home for the holidays.

The four brothers live on an island in a house with no door. Their front yard is the bank of a backwater.

We don’t know anything about this place except what we’re shown. It is beautiful and calm, but through the words of another character, a fifth man, we learn that it is close to a dumping ground for trash.

The most consequential role in the film belongs to this other character, the fifth man. He is the ‘villain’ Shammi, played with relish by Fahadh Faasil.

Shammi is a typically macho guy. He has a moustache that he likes to groom. And in contrast to the dreamy brothers, he has a job– at a hair-cutting saloon. Shammi has just begun life as a married man but he is a ghar jamai, someone who lives in his wife’s house, with his mother-in-law and sister-in-law.

Perhaps this is an emasculating position to be in, but for Shammi it is also an opportunity to be the man of the house, and as we will see, he takes this job seriously. When his sister-in-law, Baby, falls in love with one of the brothers, the curly-haired Bobby, and resolves to marry him, Shammi opposes the match. This stance creates the conflict around which the latter half of the film revolves.

Kumbalangi Nights is full of tender moments interspersed with typically male-centric scenes. When Frankie the youngest returns to the untidy home that he shares with his brothers, he cleans it up and cooks a special meal with a casualness that merits no special comment. It’s like the filmmaker is saying, “yes, it’s no big deal that a boy is doing the work that women have been doing for generations.” Yet, a few moments later, two of his elder brothers are on the floor wrestling and grabbing each other by the balls.

Shammi, the film’s ‘villain’ is the only one who’s obsessed with his manliness. In the very first shot in which he appears, he is looking at himself in a bathroom mirror, admiring his moustache, very much a symbol of virility and strength. While gazing at himself, he notices his wife’s bindi stuck to the glass. He removes it with a blade and flushes it down the sink as if its existence spoils the image before him. Apparently satisfied with the result, he gazes upon his own reflection and declares, “Raymond, the Complete Man”*.

For all its progressiveness, Kumbalangi Nights never fails to remind us that we live in a patriarchal world. Bobby and Baby fall in love but when he approaches Shammi to ask her for her hand in marriage, he is insulted by him.

Meanwhile, Saji, one of the two older brothers, is forced to wake up to reality. In a sudden rush of events, an unstable Saji tries to kill himself. But in the ensuing melee, it is his best friend—who tries to save him—who dies.

A couple of scenes later, a broken Saji–played with a luminous vulnerability by Soubin Shahir–summons his youngest brother, Frankie. After a bit of chitchat, Saji says one of the most powerful lines ever said by a male actor:

“I have completely lost my mind. Seriously, I need help. Can you take me to the hospital? I’m unable to cry.”

In the next scene, he is comforted and encouraged to purge his emotions by the doctor, yet another male character who says, “feel free to cry, I am here to help you.” Saji breaks down and sobs into his chest.

Eventually, Saji resolves to help his dead friend’s pregnant wife and encourages her to move into their house to have her baby.

If Saji’s growth is extraordinary, Shammi’s descent is shocking.

In the last few scenes of the film, we learn that Shammi is not just a garden variety creep, but also someone who suffers from psychotic breaks. As he descends into a violent episode and attacks his wife, his mother-in-law, and his sister-in-law, it is up to the brothers to save the situation. At first, Shammi proves to be too strong and too violent, but the three of them manage to overpower him.

Watching the film, especially the moving scene when Saji reaches out to his youngest brother, I was struck by the thought: how many films have we seen where one male character confides in another male character about a vulnerability? My bet was: zero. My next thought was, the world must have a Kumbalangi Test.

And that's how all of this came to be. An idle thought while watching a thought-provoking film turned into a possible lens through which to view masculinity in media—and real life.

How good is Kumbalangi Nights though? Does the film that attempts to portray a healthy masculinity itself have any unhealthy scenes?

In its evocation of male relationships and the struggles they go through, the film is pitch perfect. But there are a couple of discordant notes.

The first is the scene just after Saji’s attempt to kill himself and his friend’s resulting death. Saji is at the police station but before he is released, a police inspector walks up to him, and says menacingly, “don’t you dare do this again.” He then gives him a slap.

Saji says nothing. When the inspector follows this up with a gruff “you good?”, Saji nods his head in silence.

At one level, the policeman’s behaviour is entirely in keeping with the culture of our times. You aren’t surprised. But on another level, it is dispiriting that the filmmaker lost an opportunity here to deal empathetically with suicide.

The second letdown comes near the end of the film when the villain, Shammi, descends into madness. The brothers discover that Shammi has tied up the two women in the family. And when they try to contain him, Shammi breaks into a homicidal frenzy. But during the ensuing fight, Shammi does something puzzling: he abruptly stops fighting, and walks to the corner of a room and turns his back to the brothers (whom, as I should remind you, he has been trying to murder). He stands there in an eerie quiet.

Nisha Susan calls this scene a cop-out.

“By making Shammi into a crackpot, the filmmakers place him into a category of unhinged people.”

Until Shammi’s psychotic break, he was just a regular garden-variety patriarchal creep. Nisha says that this gives a message that “not all men are like that”. The filmmakers, it seems, missed a great opportunity to bring home the point that Shammi is a typical male, and his atrocious behaviour is not because he is ‘mad’, but because he is ‘male’.

“As a Malayali woman, you’ve heard the things that Shammi says in the film from other, real people,” says Nisha. She continues:

“While watching the film, you feel your skin crawling because Shammi’s interactions with his wife and sister-in-law and mother-in-law are all so familiar. This guy is trying to boss his sister-in-law in a weird way, and all the other things are super gross, but also super familiar. So standing in the corner and making him a little bit off, was a cop-out.”

But for these two imperfections Kumbalangi Nights would have been flawless. However, it’s worth stressing that it doesn’t need to be perfect for a Kumbalangi Test to be valid, just like the Bechdel Test doesn’t need to be a perfect test of women’s representation to be valid.

It’s not like I’m aware of too many other options anyway. Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara is brilliant in its evocation of a kinder masculinity, but it came out before I was even thinking about the topic.

Perhaps we could have had a Ted Lasso Test, given the series’ spotlight on flawed masculinity. The titular coach in the series is himself a kind and empathetic man, and so is the assistant coach, his buddy. Even the peacockish Jamie Tartt and the grumpy Roy Kent shed their shell and reveal an unexpected softness.

One reason Ted Lasso may not work is that it does its magic over three seasons that were developed over five years. Plenty of room for characters to develop complexity and nuance, and maybe because of that, Ted Lasso may be too high a bar. After all, we are trying to work out a test that is practical. What’s the point if we have a test that no film can aspire to pass?

In the end, the Kumbalangi Test works because the film it is named after does just enough.

Which brings us back to the simplicity of the Bechdel Test which is, to refresh ourselves, a test of a film in which two female characters talk to each other, about anything other than a man.

Similarly, a Kumbalangi Test could offer the following formulation:

Any film in which a man talks to another person, about any vulnerability or weakness, can be considered to have passed the test.

Surely, that’s not too high a bar.

The festival director of the New York Indian Film Festival, Aseem Chhabra has lived and worked in both the United States and India. He says it's a good idea to examine exactly how men are represented in films. A Kumbalangi Test, he says, would be useful.

“If this takes off, it's a path for scriptwriters, producers and directors to also present male characters as regular, normal human beings, not like you know in Mirzapur, the series, in which all the characters are doing is killing, killing, killing each other.”

“Films don't necessarily show flawed men”, says Chhabra, “Indian films definitely show less and less of that.”

The writer and film critic Sowmya Rajendran says this is typical of Indian movies:

“This hyper-masculine thing is very much pan-Indian. The filmmakers are male, and they assume that film-goers are also male. These are films that celebrate a very aggressive, entitled masculinity.”

The aggressive, entitled, and hyper-violent male is a staple character in several Indian films. As a rule, men are not depicted as caring, empathetic and vulnerable. If the Kumbalangi Test helps us interrogate masculinity just by talking about how men are portrayed in films, it will have done its job. Just like the Bechdel Test.

So what happens when you use the Kumbalangi formulation to review a film?

We have our very first challenge with Pushpa: The Rise. Released in December 2021, Pushpa is the story of a coolie named Pushparaj, played by the actor Allu Arjun.

I chose the film to test because it was one of the highest-grossing films of its year and a mass hit in both theatres and on streaming platforms. Moreover, the sequel Pushpa: The Rule is forthcoming, and will likely once again be the talk of the town.

In the film, Pushpa rises through the ranks, going from coolie to a smuggler of red sandalwood. Through a combination of daring and dum, he becomes the partner of a set of brothers who run a smuggling business.

Next, he takes on the big syndicate boss. This is the man to whom the brothers and all the other smugglers sell the wood. When he topples the syndicate boss, Pushpa is crowned the undisputed leader of all.

Along the way, Pushpa has several encounters with the local police, culminating in an epic battle of egos with the police officer Bhanwar Singh Shekhawat, in a typical role played by Fahadh Faasil (the same actor to play the role of the villain Shammi in Kumbalangi Nights).

Describing Pushpa as a super-hit is, if anything, an understatement. Like other Telugu films that were dubbed into multiple languages such as Baahubali or RRR, Pushpa has also seeped into our collective unconscious and its dialogues have become commonplace. While walking on a pavement in New Delhi last summer, I saw three Hindi-speaking kids heading out from school, taking turns to try out the following dialogue from the film:

“Pushpa, Pushparaj … mein jhukega nahi, saala.”

Here are some guesses why Pushpa struck a chord with audiences: pride in southern India that a Telugu film has become a pan-Indian hit; the stardom of Allu Arjun who plays the role of Pushpa with a swagger, with one shoulder raised; the song Srivalli and the viral dance trend on Instagram Reels and other platforms.

The film’s rags-to-riches story also provided a release for a population that suffered several enforced lockdowns through three waves of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Yet, it is a deeply vexing film.

A central theme running through it is the idea of legitimacy and the tragedy of not having a surname.

Pushpa’s mother is the mistress of a man who dies early, when the titular character is a young boy. As a result of the death, mother and son lose their home. When he enrols himself in school, he is cruelly prevented from taking his father’s name as a surname. When set to be engaged to Srivalli, his half-brother (who’s born in wedlock) prevents it by taunting him about his illegitimacy. Later on in the film, the policeman Shekhawat taunts Pushpa for his white brandless shirt: he points to his own shirt’s label and says,

“My shirt has a half-inch sticker. That is what a brand is. You know what a brand is right? It is a surname. It means a stamp that tells who manufactured this [shirt], who gave it birth. [This shirt] has a stamp. That’s why it has value. That one [pointing to Pushpa’s shirt] doesn’t have [a stamp] hence it doesn’t have a value.”

The idea of illegitimacy could have been solved by the filmmakers giving Pushpa his mother’s name, but then they would have lost the regressive narrative arc.

In perhaps the most shocking scene of the film, Pushpa’s romantic interest, Srivalli, is placed in a desperate bind. In order to save her father, she has to submit to being raped. Srivalli turns to Pushpa, who is presumably hurting after the engagement was denied. He tells her that he will not save her. But when Srivalli admits her love for him, his attitude is transformed. He goes with her into the bad guy’s den and thrashes him.

The writer and film critic Anna MM Vetticad, who has made it a mission to call out problematic depictions in films, writes in her review:

“…The communication is unambiguous: society’s concern for a woman’s safety, dignity and bodily integrity are contingent upon her submission to patriarchy; once she submits, he not only cares, she becomes his protectorate; if not, she deserves her fate...”

Pushpa completely and devastatingly fails the Bechdel Test.

But what about the Kumbalangi Test? In order to pass it, my formulation calls for at least one scene in a film in which a man talks to another person about any vulnerability or weakness.

In Pushpa, the angry hero speaks of his vulnerability on at least three occasions:

First, during the comic-romantic breaks in the narrative, Pushpa shows his keenness to be seen and smiled at.

Next, when his engagement is interrupted and his mother suffers an injury to her head, he rushes her to the hospital. This scene is intercut with a flashback to when Pushpa was 5 years old and is, along with his mother, unable to attend his father’s funeral. Later in the scene, he tells his loyal lieutenant Keshava,

“I was just a 5-year-old then. I didn’t even know how to fight. These guys have created all kinds of troubles and took away whatever we had. My father had given me a gold chain for my birthday. In that chain, there used to be a photo of me and my father. That was the only thing I had as a memory in those things. They took that away as well.”

This recollection leads to anger, and Pushpa spouts the dubbed Hindi dialogue that we encountered earlier, “Pushpa, Pushparaj … mein jhukega nahi, saala.”

The third example of vulnerability comes towards the very end of the film when Pushparaj, in a bizarre turn, is having a drinking session with his nemesis, the police officer Shekawat.

Pushpa asks: “Sir, you said you will decide when my wife will get pregnant, and at what time she will get pregnant. Sir, why did you say that? Tell me sir why you said that? I felt very bad.”

Shekhawat responds to Pushpa: “Why are you spoiling the party mood? Why all that now?”

“It’s okay sir, you must have said it to hurt my feelings. Isn’t that it? Let it be. But…I don’t like the way you insulted my mother sir.”

In the next scene, Pushpa grips the barrel of Shekawat’s service revolver with one hand, and shoots himself in the palm. He opens his fist to reveal the bloody wound the bullet has created. Referring to the blood, Pushpa says, “my father gave me this [blood] even before my brothers could snatch the surname from me. No one can separate this from me. This is my…brand.”

Pushpa: The Rise has a problem which it shares with other such films. There is a progressive arc that can be described like so: It shouldn’t matter whether a child has been born out of wedlock or not. What matters are the child’s actions. But the plotline of the film is straight out of the 1980s potboiler playbook.

So, does Pushpa pass or fail the Kumbalangi Test? The hero is vulnerable alright, but his vulnerability leads to an anger that is corrosive and toxic to everyone else around. The only emotions Pushpa himself can access are anger, which has for long been the only emotion men are ‘allowed’ in popular culture. Even the brief moments of sadness leads to an entitled anger.

I used the term vulnerability but it isn’t that really which drives Pushpa in the three scenes. Rather it is a sense of victimhood or angry self-pity, which is another emotion that men are allowed to access in popular films.

We cannot confuse victimhood with vulnerability.

Keeping that in mind, Pushpa fails the Kumbalangi Test.

There might be other films however, that pass the test in letter, but not in spirit. And those that pass the test in spirit, but not in letter. This is fine, because we don’t just learn from films through dialogue, but also through facial expressions, mood, atmosphere, character, music, and sound effects. Films are powerful precisely because they allow us to experience things we might not be able to experience otherwise.

Ultimately though, the point of the Kumbalangi Test isn’t whether a film has passed it or failed it. The point is to help us understand how masculinity is portrayed in films and whether anything ought to be done about it.

Still, I can’t help but ask a question. Given the challenges of a film like Pushpa, should the Kumbalangi Test itself be altered?

My original formulation was: any film in which a man talks to another person, about any vulnerability or weakness, can be considered to have passed the Kumbalangi Test.

We can amend that further by removing the word ‘weakness’ and by adding ‘anger’ and ‘victimhood’.

So then, to pass the Kumbalangi Test then, a film ought to have

a man who talks to another person,

about any vulnerability,

other than anger or victimhood.

It’s been three years since I first saw Kumbalangi Nights and thought about the need for such a test. In this period, my understanding of unhealthy masculinity has evolved further. One might say, the pendulum, having swung the other way for me, is back near the centre. I find some aspects of masculinity as it is portrayed to be unhealthy, but there are others that can perhaps be ignored for now (strong, silent tropes) or worth keeping (shadings of stoicism).

I also now feel the need for other kinds of tests.

One such test could be about the representation of various castes and Adivasis in our films. Such a test could be named for landmark anti-caste films such as Samskara (1970) and Ankur (1974), or more recent films such as Fandry (2013), Masaan (2014), or Sarpatta Parambarai (2021). (As a savarna male, I’ve not experienced any caste discrimination, and indeed might have unwittingly passed some on. This makes it difficult for me to pick the right film for such an anti-caste test.)

Another test could call for a better distribution of high value roles to speakers of multiple dialects per language. (I can recall Kannada, Hindi and Tamil films in which the speakers of rural dialects are invariably absurd characters.)

Such tests, along with the Bechdel and Kumbalangi Tests could point the way towards better diversity and representation in our films, and outside of celluloid, a more equal voice for all types of beings.

(Edited by Jayaprakash Satyamurthy, Malayalam translation fact-checked by Joseph John. Acknowledgements to Supriya Nair.)

The Kumbalangi Test sets a low bar, yet very few films can hope to pass it (for now).

Do you want to review a film using the Kumbalangi Test? Join me here or on Instagram Reels and YouTube Shorts. In the next few weeks, I’ll be adding posts and videos on other films.

Thanks for a well elucidated analysis that common movie viewers (not just the elite critics) can appreciate. I was beginning to be a little disappointed with the original formulation of your Kumbalangi Test but you redeemed it with the final enhancement.

Two other cultural memes that cinema (especially Hollywood) must be measured and held accountable for propagating and normalizing are: (1) throwing objects and smashing them against the floor or a wall or glass to show anger or frustration sometimes for trivial matters and often by actors whose role otherwise has no personality attributes matching this action, and (2) throwing food items into the bin after taking a bite, or, elaborately pouring two glasses of a drink after one person asks if the other wants a drink, and then immediately, leaving both drinks and going out.

Very impressive. Rich with insightful thoughts. I felt like reading this masterpiece again and again until each word gets tattooed on my mind.