Consider a river, any river. Whatever you do to it upstream (dam it, poison it, suck it dry) affects it downstream. In the same way, any act of censorship upstream, however small, can have huge effects downstream. By ‘upstream’, I’m referring here to acts by the government, and by ‘downstream’, I refer to the resulting actions of the people.

So upstream actions tend to create a culture of fear that spreads disproportionately wide. This is known as the ‘chilling effect’. The term comes from the American legal world and its invocation has resulted in the creation of case law or legal precedent, especially in cases related to libel.

According to the Collins Dictionary, ‘chilling effect’ is defined as

a discouraging or deterring effect, esp. one resulting from a restrictive law or regulation.

My focus here is on censorship and freedom of speech. In India and other countries where the press is only partly free or not at all free, the chilling effect is widespread. But it is important to note that the chilling effect isn’t just about the press:

- Survivors of sexual harassment may be reluctant to press charges because the system is rigged against them.

- At workplaces run by dictatorial bosses, colleagues may be reluctant to provide important and crucial feedback.

- Worries about technological and/or governmental surveillance may lead people to censor themselves on social media and on WhatsApp.

These three are among innumerable examples of the chilling effect.

Is the press in India censored?

This question cannot be answered fairly without taking the chilling effect into consideration.

On paper, the press is India is not censored. At least officially, journalists don’t have to show pieces to someone from the government before publishing them. In other words, there is no ‘prior restraint’. The advocate Abhinav Chandrachud writes in his book Republic of Rhetoric: Free Speech and the Constitution of India:

A prior restraint is a form of censorship imposed before the publication takes place. For example, if the government directs newspapers not to publish any articles unless they are first approved by the government, this form of censorship would be called a prior restraint.

Prior restraint apart however, there’s plenty of censorship of other kinds in India and other countries, which leads to the chilling effect. Here’s a short list:

Laws, especially criminal laws such as sedition.

Court action taken suo motu (on its own, without a plaintiff) and the admittance of flimsy cases.

Police action, especially the filing of FIRs (First Information Reports) by the police.

Speeches by politicians.

Threats of legal action by various parties.

Censorship by mob, such as trolling online by individuals or groups.

Cultural norms that create a culture of intolerance and fear.

Pliant media, who’re sharply critical of any criticism of the government.

Real or perceived surveillance by the government and/or technology companies.

Private entities.

This last point is worth elaborating on. Under the Constitution, Indians are guaranteed the right to free speech (with exceptions), and at least in theory, Indians can look for legal remedies from governmental action. However, there is no such right to free speech when it comes to private bodies such as corporations.

Chandrachud writes,

This is particularly problematic in a place like India where threats to free speech often come from private, non-state actors. India’s most famous painter, M.F. Hussain, lived out his last days in self-imposed exile, because of death threats he received from vigilante groups in India—groups that were offended by his nude paintings of Hindu goddesses—despite a decision of the Delhi High Court quashing warrants of arrest and summoning orders issued against him.

So even if restraints are not imposed by the government, and even if courts come to your aid, you can still be harassed. The chilling effect goes far indeed.

So what?

We might hear the argument, so what? So what if there’s a chilling effect? Some topics shouldn’t be talked about. What does it matter?

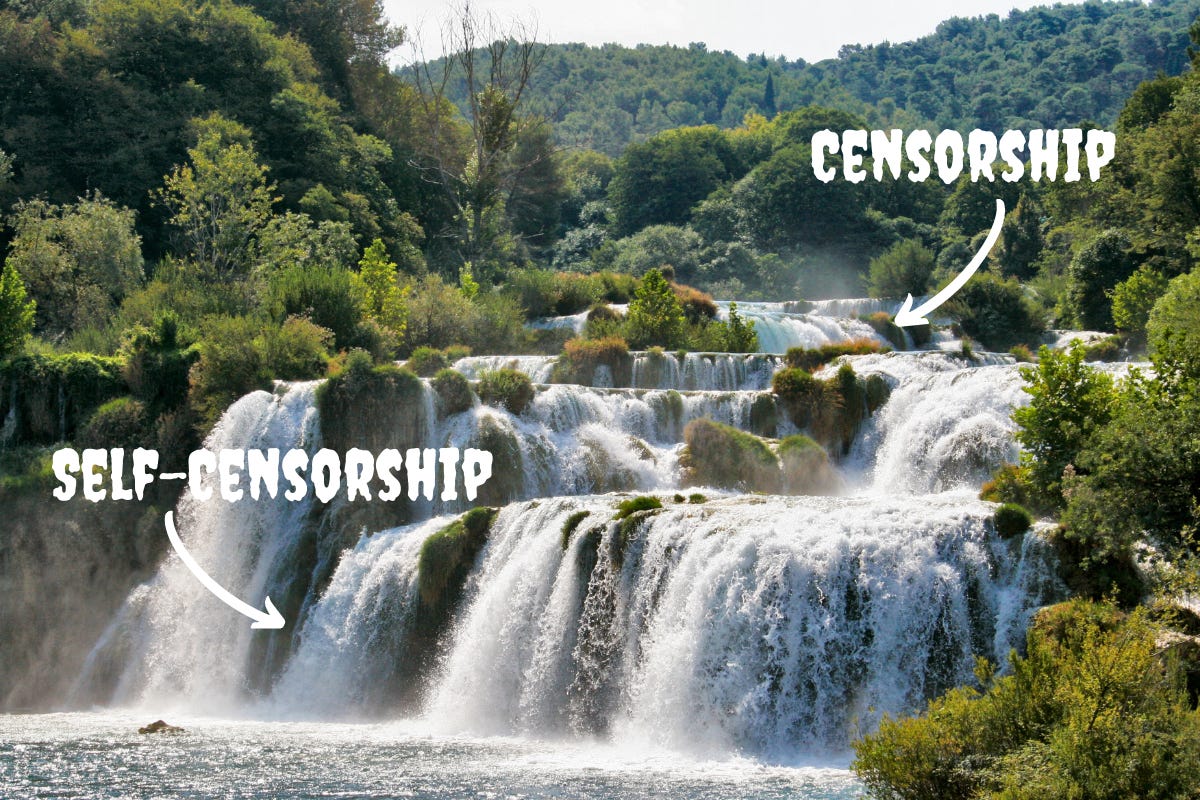

Other than the fact that free speech should be considered a basic human right, there are unanticipated consequences of the chilling effect. Censorship often follows the following pattern:

As the graphic shows, self-censorship is not the end-result of the chilling effect on speech—it is merely a stop. Inevitably, people who censor themselves from making their thoughts available to others start practising thought-censorship like so: It’s far too painful to keep stuff in my head. Better to stop thinking along these lines altogether.

Thought-censorship becomes a survival tactic.

When you see self-censorship and thought-censorship at scale, you also begin to witness the death of ideation. No society can innovate its way out of its crises without fresh thinking and ideas. But if the cost of thinking out-of-the-box is high, where’s the incentive to do so?

There’s a lot of myth-making when it comes to the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment in the West. But one thing seems clear: as speech became freer, more and more ‘forbidden thoughts’ led to radical advances in knowledge.

The faster we see the links between censorship, the chilling effect and the death of ideation, the better it is for progress. Not to mention the fact that the availability of this most basic human right will make our lives better.

Image credits: H R Venkatesh