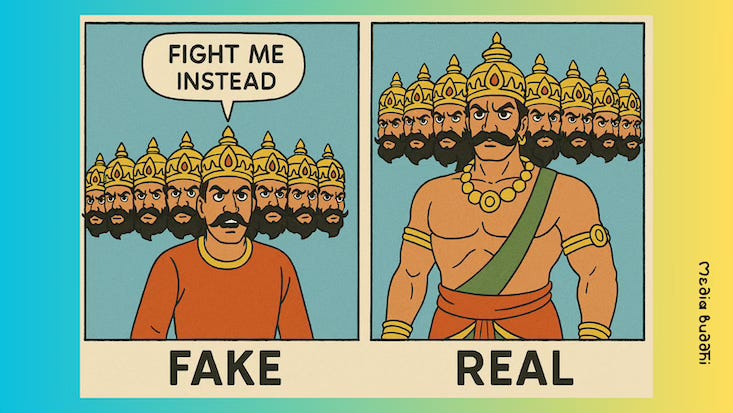

As you can see in that cartoon panel above, there are two Ravans (or as we say in the south, Ravanas).

One of the two Ravans is labeled ‘fake'.

This fake Ravan is saying “fight me instead”; whereas the real Ravan is saying nothing.

The two Ravans are metaphors. They are things that stand in for other things.

I love metaphors, but this tendency of mine drives some people mad, such as my teenaged son. “Just tell me you’ve been on the computer for too long”, he might say, “instead of saying my screen time is the line at the Tirupati Devasthanam!”

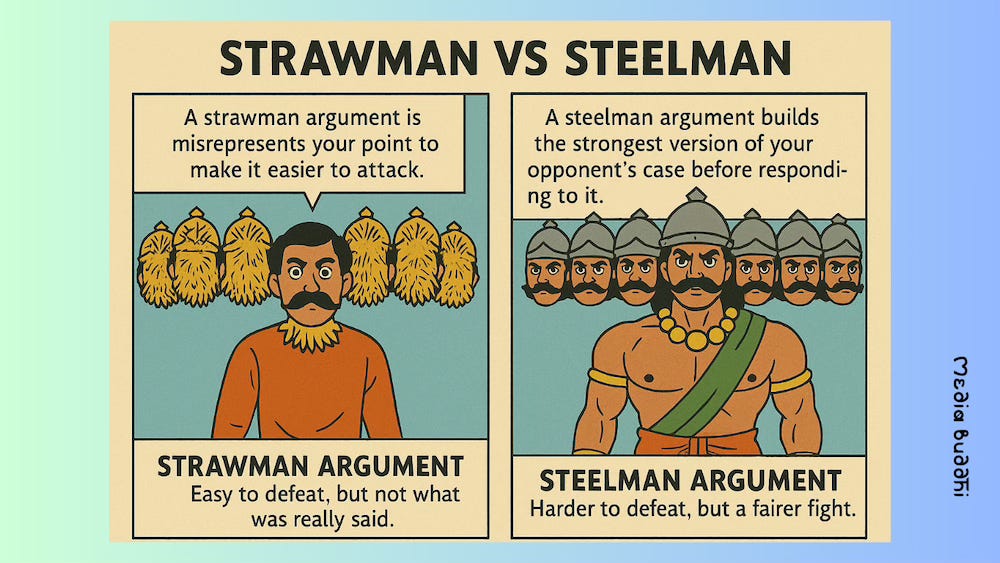

Sometimes though, metaphors are quite useful. And the two Ravans are metaphors for two concepts that I find very useful — the strawman and the steelman.

Let me illustrate with an example.

Hindi in southern India

Say you’re out in Bengaluru having dinner with friends from work, and the conversation turns to hobbies and interests. One of your friends, let’s call him Sumit—mentions that he is a reader of Hindi novels, and that he feels sad that English is still, after all these years of independence, more preferable than Hindi.

To this, you and the others around respond politely, but the conversation starts getting heated as more and more people chime in. After all, this is the south (side-fact: Bangalore is more south than even Chennai), and the conversation snowballs into a raging debate.

Meanwhile one of the others in the group, an excitable old mate of yours from school, adds some uppu-khara1 to the whole situation and says loudly, “hey aren’t you a Kannada enthusiast? Don’t you think you should say something to Sumit?”

You decide to jump into this debate. At this point, you have two choices.

Your first choice is to deliberately weaken Sumit’s argument by saying something obviously emotional and untrue:

“All you Hindi supporters are supremacists. You want to erase South Indian languages.”

“You guys only want government jobs to go to Hindi speakers so you can create a monopoly.”

In truth, Sumit did not say any of the above, but you’ve twisted his argument a bit, and you’re now responding as if he had said something like the above.

This is known as a strawman argument.

I’ve had very many strawman arguments with people over the years. I have used such arguments myself. They have not helped.

Your second choice is to approach this with a steelman argument, which requires you to take up the strongest part of Sumit’s argument seriously.

So you respond with:

“I wonder what makes you feel that way. Since I’m passionate about Kannada, I can understand your love for Hindi.”

With such a start, an eventual conversation between you and Amit might go on like this:

Sumit: People think Hindi is one big mass but the diversity of voices and dialects within it is remarkable. Writers like Premchand and Geetanjali Shree occupy different universes but they echo social realities that resonate all across India. I feel we miss something when we prioritise English over Hindi.You: 100% man. And it's the same thing with Kannada too, from Kuvempu to Vivek Shanbhag and Banu Mushtaq. Sumit: Interesting! Of course English is more practical and it offers economic advantages. But there's also a colonial hangover at play here. You: I agree with you. Language diversity is one of India's strengths. My only concern with promoting any single language nationally is that it might unintentionally diminish others. In southern states, our language is tied to our identity and sense of pride.Sumit: How could I not notice that, having lived here for 2 years! I wouldn't want Hindi promotion to come at the expense of languages like Kannada, Tamil, Malayalam, Marathi or any other. I guess I feel a sense of loss because I live here and am far away from home. And to be totally honest, I lost two aunts during COVID and that feeling I have is tied into all of this. You: Sorry to hear that. And let me assure you — what you see us as reacting against, is not Hindi in itself, but the perception of imposition. Sumit: That makes sense. I hadn't fully considered how language policies might feel imposed rather than offered. We should create opportunities for speakers of all languages. You: Exactly. I think digital technology is making this more feasible than ever. And so on.

The conversation above incorporated a steelman approach because:

It allowed both parties to engage with the strongest version of each other's arguments.

The two parties did not assume the worst of the other.

They tried to understand each other’s values and find common ground where possible.

They acknowledged each other’s concerns.

I realise that it doesn’t feel practical, but I think we lose an opportunity every time we resort to strawman arguments. They make us feel virtuous yes, but they don’t serve any other purpose other than make us feel a fierce belonging to a particular group or cause.

Enter the Ravans

The problem is that frameworks like the strawman-steelman approach are not easy to convey in the Indian context. They are metaphors, and metaphors that lack context or imagery don’t work well.

I wondered if I could come with a metaphor that works in India.

I turned to generative AI to suggest a few alternatives to strawmanning and steelmanning. Here are some of them:

Hindi/Marathi: Kachra mudda (strawman) vs Tagda point (steelman) [Tod-marod = twist and distort]

Hindi: Tod-Marod point (strawman) vs Izzatwala point (steelman) [Izzatwala = respectful]

Kannada: Jollu Vaada (strawman) vs Gatti Vaada (steelman) [Jollu = hollow; Gatti = strong]

These are all serviceable but I felt they were not memorable enough. And then I had a flash of insight. During Dussehra every year, effigies of Ravans are set on fire. Could they work as metaphors for strawman and steelman?

It turned out that they could. With a little bit of fiddling.

So there you have it. Anytime you witness someone deliberately or unconsciously misstating your core argument, tell them not to fight fake Ravans or in Hindi, tum nakli Ravan ko math jalana.

And tell them to fight the real Ravan instead, that is, asli Ravan se ladna.

And so to complete the sentence,

Nakli Ravan ko math jalana

Asli Ravan se ladna.

From steelmanning to Purva Paksha

It turns out that right here at home in the Indian philosophical tradition — specifically the Nyaya school of thought — there’s a concept that is vaster than steelmanning.

This is Purva Paksha.

But before we get into what Purva Paksha is, let’s get into what it is not. It has no connection to Shukla Paksha or Krishna Paksha which refers to the waxing and waning of the moon. No connection to Pitru Paksha either, which is the period every year after Ganesh Chaturthi when one honours one’s ancestors.

Purva Paksha simply means ‘former viewpoint’.

It refers to the practice of understanding an opponent’s point of view thoroughly, and so completely that you can restate their view better than even they can.

Only once you do this can you present your own case, which would be known as Uttara Paksha.

It is said that Purva Paksha was used by Sri Adi Shankaracharya to defeat his opponents in a debate, and that in turn, Sri Ramanujacharya used this principle to further refine the Shankaracharya’s teachings.

However, I prefer the Nakli Ravan/Asli Ravan framework to Purva Paksha for a four reasons.

One, Purva Paksha seems more suited to formal settings. The nakli/asli Ravan framework is easier to convey during furious dinner party conversations and WhatsApp debates. Moreover, Purva Paksha is a tool that seems better employed to defeat someone in a debate. But if your purpose is not to defeat but rather to understand, then the nakli Ravan/asli Ravan framework is more suitable.

Two, Purva Paksha doesn’t evoke an instant image in our heads.

And three, my own lack of understanding of Purva Paksha makes me hesitate. Most online entries reference the work of Rajiv Malhotra’s Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism. But Malhotra’s book doesn’t provide reference material for this, and I have not been able to find any other original English writing on the subject. Most other online sources link back to this book.

Thus far, I’ve combed through the indexes of two massive works: The History of Dharmashastra by P V Kane (7 volumes) and the Brill Encyclopaedia of Hinduism (6 volumes). The latter refers to it once but doesn’t explain it.

The next step is to find a guide to existing tracts on Purva Paksha in Sanskrit and other languages. If you know someone who can help with his, do let me know!

An example of the Nakli/Asli Ravan framework

Here’s how advocates both for and against reservation might use Nakli Ravan arguments:

For: "Those against reservations are basically upper-caste elites who want to keep Dalits and OBCs oppressed."

Against: "Those for reservation just want freebies without merit."But the very same people will get further if they use an Asli Ravan framework to advocate for either position:

For: “We must continue to break down barriers to correcting historical injustices.”

Against: “Let us refine reservations to remove newer inequalities.” One possible limitation of the Nakli/Asli Ravan framework is that it may not evoke an instant image in the minds of people in areas of India where burning a Ravan effigy is not a regular practice. I do think however, that this being the age of information and instant Internet, it’s not a huge issue.

At any rate, that’s why I used the North Indian spelling of ‘Ravan’ instead of the South Indian (and my preferred) spelling of ‘Ravana’.

I test the Nakli/Asli Ravan framework

25th April 2025: During a heated WhatsApp discussion with my school classmate Rashmi Hariharan, I decided to test the framework out.

The topic is irrelevant for the moment, because it will only serve to distract us, but at one point, I referred to her as "a champion of fighting fake Ravanas".

Possibly it was the way in which I conveyed it, but she initially misunderstood completely - thinking that I was comparing our discussion topic to the king. This led to some confusion where she defended Ravana as having more principles than the people we were discussing! (No arguments there.)

The breakthrough came when I asked if she wanted to know what I meant by the phrase.

Despite the messy, circular nature of group chat conversations (complete with audio notes, scolding, playful threats and hooting from other friends), I walked her through the metaphor step by step.

Eventually, I explained: "Those Ravana effigies we burn aren't the real Ravana - they're simplified versions that are easy to defeat. In our arguments, whenever I make a point, you often respond to a simplified version of what I actually said - like fighting a fake Ravana instead of engaging with my real argument."

The framework seemed to resonate once properly explained, though it required patience and persistence to get through the initial confusion and emotional heat of the moment.

19 June: Did it stick?

Almost two months later, I rang up Rashmi to ask if she remembered our conversation. Her response revealed the framework had genuinely resonated.

"Yes you were talking about it, I remember," she said, adding her own insight: "It's an everyday matter. This kind of thing happens at home, between mother-in-laws, daughter-in-laws - lot of interpretations happen on an everyday basis when misunderstandings happen."

She even switched to Kannada to emphasize her point: "Yenilvo adanne thogondu fight maadthare" (They pick up something else entirely and fight about that).

The metaphor had not only stuck, but it had also helped her recognise a pattern that occurred in daily life beyond our own arguments.

So how would you use this Asli/Nakli Ravan framework in your language? Is Purva Paksha still a better term? Or should we stick to the Strawman-Steelman version even for Indian contexts? I’d really, really love to know what you think. If this piece resonated in some way, do leave a comment or write back to me.

Note: Ravan images generated by AI.

Uppu-khara means ‘salt and spice’ in Kannada. It’s like saying ‘he put some more masala to the conversation’ or ‘he put chavi to him’.

Agree with your differentiation. Your framework's goal is to find common ground. Purva-paksha is generally used to represent the opposing view as faithfully as possible before addressing the lacunae in that argument.

You will find more details of purva-paksha in this book https://www.amazon.in/Theory-Practice-Studies-Debates-Dialogues/dp/8124608563

I didn’t know what you meant by fake Ravan when you first mentioned it (and the AI images didn’t help). Only when you wrote that it referred to an effigy of Ravan that the penny dropped. So, I would probably prefer ‘Ravan ka putla’ in Hindi (putla = effigy) instead of nakli Ravan.

I think it’s easier to understand this analogy than strawman/ steelman or purva paksha.