Imagine that you’re a gardener. A gardener who is careful about what goes into your garden and what needs to be weeded out.

The popular stereotype is that gardeners are unbending, fussy, and stubborn with strong notions about what should go into the soil and what should be rooted out. In reality, gardeners are often innovative, flexible and experimentative. What unites all of them, however, is their constant tending to their gardens.

The process of decolonising the mind is exactly like tending to a garden. You have to be careful about what you weed out of your mind-garden and even more selective about what you decide to plant. And you must constantly, like a gardener would, tend to your mind.

To decolonise, writes the academic Neil Larsen, “means to “eliminate the racism from”.

I find this a pretty useful, but in our current political context in India, I would add four more words:

To decolonise is to eliminate the racism from within our own minds.

(This is still an incomplete1 definition, but it will suffice for now.)

Decolonisation is a buzzy term these days. It seems like we can scarcely go a few minutes before someone on WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube or TV shouts at us to discard colonial narratives, reframe history, or fight cultural corruption.

But most of what masquerades as decolonisation is not actually decolonisation at all, but rather politics in disguise.

To illustrate this point, let’s examine three examples and see what they can teach us.

1. Politics masquerading as decolonisation; Or decolonisation that is only in name

A few lunar cycles ago, my 78-year-old father sent me a video asking me to watch it. Here’s something you should know about my father: if someone praises him or says nice things to him, he immediately wonders why they are ‘buttering him up’.

In other words, my father is a naturally sceptical man who is wary of most ideologies. Which is why it surprised me that he was consuming so much content from an influencer whose videos routinely go viral.

The influencer in question is Keerthi, (she prefers not to use her second name). And she describes herself as “a history graduate who wants to tell the real history of India that the education system has forgotten”. Her YouTube channel Keerthi History boasts some 2.25 million subscribers, which makes her a part of influencer royalty.

The video is titled, It’s a shame that we have been doing this for 75 years! But what truly grabs your attention is the bold text that screams, DECOLONISE INDIA.

In the video, Keerthi begins with a now-familiar refrain. “It’s been 75 years since we got independence,” she says, “but the colonial mindset, the inferiority complex is still there in the minds of India.”

The very idea that we Indians harbour an inferiority complex is infuriating. Naturally one would like to know more!

But it turns out that this is no investigation into the colonised mind. Instead—despite her use of the word “decolonisation”—it is a hype-filled tribute to Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In words that seem copy-pasted from a thousand WhatsApp forwards, she begins, “For more than 65 years, the government did not make any effort to erase the symbols of slavery”.

She continues:

“Thankfully, since 2014 after Prime Minister Modi came to power, significant initiatives have been taken by the government to decolonize India. To restore India’s glorious heritage. I’m going to list the 7 most impactful things the government did since 2014 to decolonize India.”

Keerthi proceeds to list these seven ‘impactful things’:

Replacing the hymn Abide With Me with the song Ae Mere Watan Ke Logon at the Beating Retreat ceremony held at the end of Republic Day celebrations every year.

Changing the Indian Navy’s ensign: The previous ensign featured the Indian tricolour with the Cross of St. George. The new ensign replaces the Cross with the Indian emblem.

Renaming the road connecting Rashtrapathi Bhavan and India Gate from Rajpath to Kartavyapath.

Installing the statute of Subhas Chandra Bose at India Gate.

Replacing the Finance Minister’s budget briefcase with a pouch called the ‘Bahi Khata’ during the annual budget presentation.

Renaming three Andaman Islands from Ross Island, Neil Island, and Havelock Island to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Dweep, Shaheed Dweep, and Swaraj Dweep.

The UGC recommendation to change ‘western’ convocation robes to handloom clothing made out of khadi.

While these changes are impressive at first glance, they fall far short of true decolonisation. Renaming roads and changing uniforms are, at best, superficial alterations that barely scratch the surface of India's colonial legacy.

True decolonisation of the mind involves a profound shift in thinking patterns, self-perception, and cultural values. It requires critically examining and reshaping educational systems, economic structures, and societal norms that still bear the imprint of colonial influence. These seven changes, in contrast, are primarily political gestures designed to evoke nationalist sentiment rather than foster genuine intellectual and cultural independence.

Take, for instance, the switch from a budget briefcase to a 'Bahi Khata'. Keerthi presents this as a triumph of decolonisation, conveniently ignoring that P. Chidambaram, as a UPA minister, regularly quoted Thiruvalluvar during budget presentations. This selective amnesia reveals the political motivations behind these so-called decolonisation efforts.

Moreover, decolonisation is not a checklist of isolated actions but a continuous, incremental process. Each step should logically lead to the next, gradually dismantling colonial mindsets and structures. The changes listed here lack this coherence and depth. They're more akin to changing the nameplate on our garden while leaving the colonial plants and soil untouched.

Keerthi's portrayal of these changes as groundbreaking decolonisation efforts, while attacking previous governments, is disingenuous at best. It lacks nuance, ignores historical context, and conflates political showmanship with meaningful cultural reclamation.

In essence, what's being sold as decolonisation is, in reality, a political strategy draped in nationalist garb. It's a distraction from the real work of decolonisation – the careful, thoughtful process of weeding out internalised colonial attitudes and cultivating a truly independent Indian identity and worldview.

2. Colonialism re-packaged as decolonisation

As of this month, three new criminal laws have come into effect, having replaced the earlier versions.

The Indian Penal Code is now the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023

The Criminal Procedure Code is now the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023

The Indian Evidence Act is now the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023

While there are significant concerns about these laws, my focus here is on the government’s claim that they replace British-era provisions with Indian ones.

But do they really?

Speaking on 19th June, after the Indian election result, the Supreme Court advocate Indira Jaising argued otherwise: “If you see the content of the laws, [it] is the repackaging of English Common Law and a rewording of the sections in the law, a reintroduction of sedition in the Indian Penal Code, a reintroduction of Unlawful Activities Act…”

According to Jaising, Lord Macauley’s Indian Penal Code is still extant in our new laws, both in letter and spirit. It’s basically old wine in a new bottle.

Jaising is a critic of the laws and an activist for the Constitution of India, and that position makes her a critic of the Modi government, but should that be a reason to disregard her words?

This approach to ‘decolonising’ India — changing sections, renaming terms, etc. while maintaining their substance — raises questions about the depth and sincerity of such efforts.

For example, the new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita retains the controversial sections relating to sedition — only, the word ‘sedition’ has been removed. The government claimed that sedition is no longer a part of the code, but what has been added instead, is a new provision that criminalises, “acts endangering the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India”. This, according to the writer, journalist and activist Aakar Patel “reads the same as the old sedition law.”

This example also throws up a broader pattern: the co-opting of ‘decolonisation’ for political gain, rather than genuine cultural and institutional transformation.

3. Genuine decolonisation without using the word ‘decolonisation’

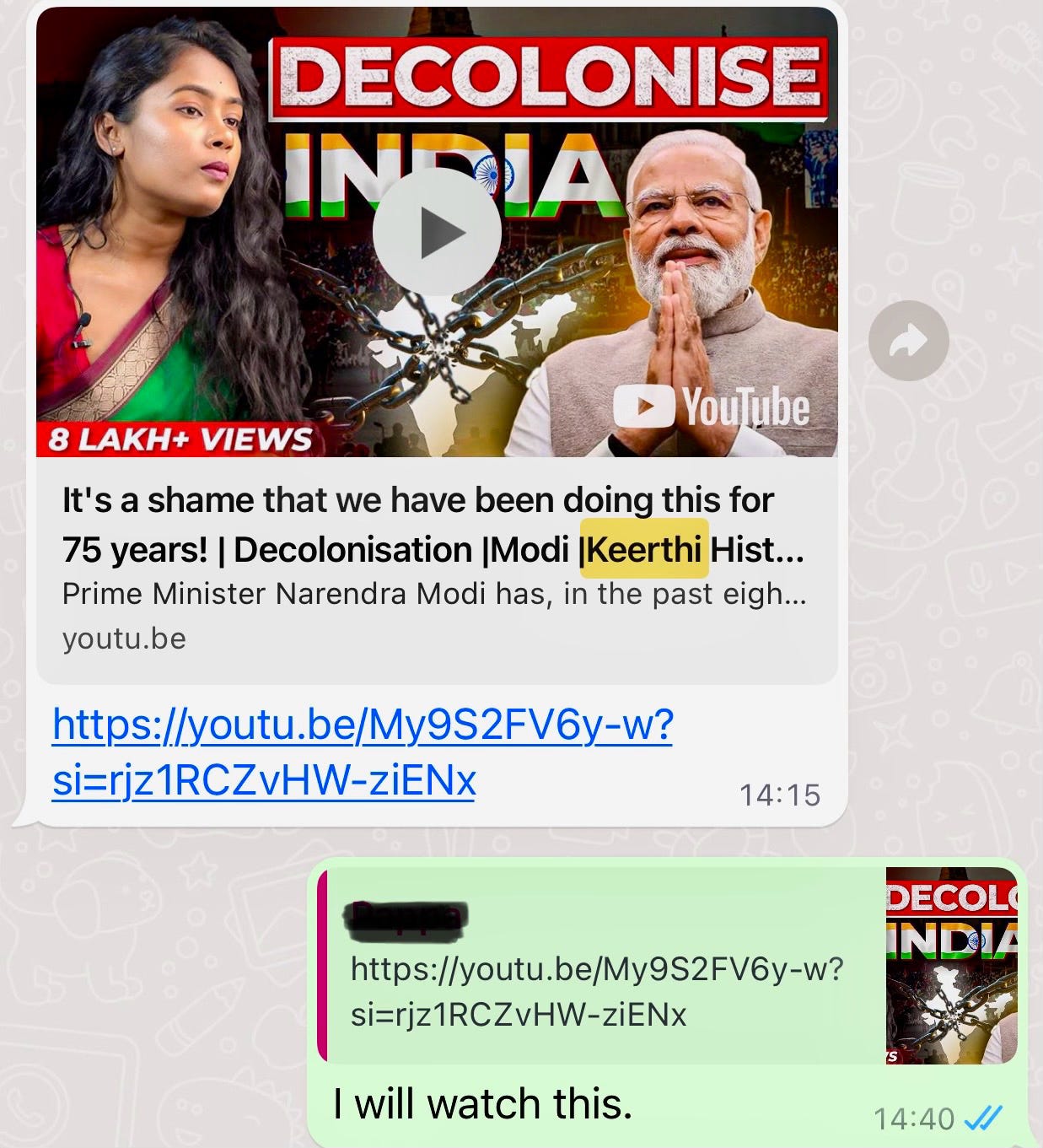

Finally, let’s examine the approach of writer Amitav Ghosh in his latest book Smoke and Ashes: A Writer’s Journey Through Opium’s Hidden Histories.

Smoke and Ashes is the story of opium and the central role of the British Empire in weaponising its use against the Chinese, via India. I read most of the book in August last year while on holiday in the backwaters of Kerala, when I was first introduced properly to my niece and nephew.

Since my niece is old enough to be curious about books, I could have explained the story of the book like this:

See, the British did a not very nice thing. They forced the Chinese to take opium for years and years, and they forced Indians to make this opium. This made the Chinese people very sick in a way that they wanted more and more of it and they could not live without it. The British did this in the beginning to get tea but actually they made so much money from opium— imagine thousands of chests of gold—they didn’t want to stop. The Chinese emperor tried to stop this import of opium, but the British forced a war against him.

In the process, some Indians in Mumbai, especially the Parsis, and a big chunk of Boston-living Americans made lots and lots of chests of gold too. In fact, a surprising bit of America’s history is linked to opium. The grandfather of FDR, one of the US’ greatest presidents’, made a fortune out of opium. So did Forbes, who they named a great capitalistic magazine after.

All this created a big, big problem that we are still dealing with even today. All this because of a little opium flower.

My niece happens to be half-Indian, half-Chinese, and 100% American, so I can argue that it might have been appropriate if I had actually said all of the above, but I didn’t. Maybe someday when she is older…

Back to the book. Ghosh peels away all notions of British fairplay with a surgeon’s skill.

The British created elaborate myths and narratives to justify the opium trade. These myths served to hide their own role in forcing entire populations into addiction cycles.

More specifically, the British used narratives that shifted the “blame away from the British Empire to its victims”. For example, they argued that the Chinese were addicted to opium because of their ‘weak’ character. Ghosh writes, “It was often said that a propensity for drugs was characteristic of 'Asiatics' in general, and of the Chinese in particular, because they were 'effeminate' by nature and hence more inclined to indulge in opium.”

They used disingenuous arguments to support their own position. For example, they argued falsely that the opium trade existed in India much before them and cooked up the idea of a pre-existing Mughal monopoly. Ghosh demonstrates convincingly that this was a lie.

Another example of this disingenuousness is their argument that opium was not illegal because there was no law against it: “Those merchants were perfectly aware of China's laws, and they knew also that they would have been reviled by their families and peers if they had sold vast quantities of high-grade opium in their own countries.”Even the practice of writing history was in service of the empire. Ghosh writes, “the idea of ‘History’ as it developed in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe was used to conceal the role of opium.”

Ghosh cites the ground-breaking work of historian Priya Satia, “British colonialists in this period developed a whole range of techniques for the 'management of conscience, of which not the least important was the idea of 'history' as a trajectory of continuous progress.”

Ghosh emphasizes that the role of opium in sustaining colonialism has been forgotten “because European empires have been astonishingly successful at whitewashing the historical record.”Finally, colonial powers even took credit for the success of the anti-opium movement. They were, writes Ghosh “have always been proficient in shaping historical narratives. This was the case also with abolition: just as the role of black resistance to slavery was, until recently, written out of the dominant narrative, so too has the story of drug regulation generally been presented as one in which Christian missionaries and Western statesmen were the chief protagonists.”

In the book and in accompanying publicity tours, Ghosh has used the following lines to describe Britain’s central role in the opium trade:

- a narco-state, comparable to Medellin,

- a criminal enterprise,

- ‘utterly indefensible by the standards of its own time as well as ours’.

The Ghosh way

Smoke and Ashes made me angry. I was appalled that the British empire did all this, and more. I also noted some things Ghosh does not do in the telling of this tale: he does not set out to stir up my emotions deliberately; that just happens as an organic consequence of the story-telling. And he does not manipulate my feelings to justify support for a particular kind of politics.

Reading Smoke and Ashes does make you hate what the British did in the past, but it does not foster hatred towards contemporary British people.

The Ghosh method, in other words, is to step away from labels like ‘decolonisation’ and simply tell a story that urgently needs to be told.

This was confirmed by Ghosh himself. On 8th February earlier this year, at the launch of his book at London’s Kew Gardens, I asked him a question about the politics of decolonisation in India, this is what he said,

“The instrumentalization of decolonization…in service of majoritarianism is something I find absolutely repellent. It really disturbs me, and I think it misrepresents everything. And it's creating all these bizarre, right-wing narratives in India. So I don't want to have any truck with that. At the same time, you know, I don't think in my book, in this one, you'd ever see the word, decolonialism. So I generally try to steer clear of that jargon, tell the story.”

- Amitav Ghosh

So which of these three strands of decolonisation should we embrace?

The first, by Keerthi History, is what I would call politics masquerading as decolonisation. The real target of this approach is the political other, or in this particular example, the Congress party.

The second, which are the new set of criminal laws, might be described as colonial attitudes to crime re-packaged as decolonisation.

The third approach doesn’t use the term ‘decolonisation’. But Ghosh’s work questions the British in the most thorough manner without succumbing to any narrative of hate or exceptionalism. It is complex, subtle, and vast in its scope.

This last approach is the one I aim to embrace moving forward.

I started this piece by saying that a good gardner would instinctively understand the slow and messy process of decolonisation. I think we can add one more analogy to this.

Not only must we choose what plants to grow in our mind-garden, but also we must be mindful of weeds. Especially weeds that belong to invasive species. Party politics, rage and hatred have no place in decolonisation, because they are the equivalent of invasive species in the garden. If we let them into our minds, they will invade everything.

To decolonise is to eliminate the racism from both within our minds and from without. It is both internal and external.

A very nice piece, though I don't fully agree with the picture. Can DM you a couple of things I have written on this, if you like!

Enjoyed reading! You've probably read the books in Amitav Ghosh's Ibis trilogy as well.