How Can We Fact-Check Something That Is ‘Not Fact-Checkable'?

And how might we do so, free of biases? Introducing the 'Story-Check' (alpha).

In the world of fact-checking, one often encounters items that are essentially not fact-checkable. These items—pictures, videos, text, audio, or a combination of them—often carry ‘fake news’, or propaganda, or may consist of polarising messages. But what sets them apart from the misinformation that can be fact-checked is that they often have no relation to facts whatsoever. (A lie has a relationship to the truth in that it’s the opposite of the truth.)

For example, at BOOM we recently fact-checked a video purporting to show jet aircraft shooting down a spy balloon. It turned out to be a simulation, and not the real thing. My colleague Srijit Das was able to track down the original simulator (Digital Combat Simulator or DCS) onto a gaming video channel, and was thus able to label the claim as ‘false’.

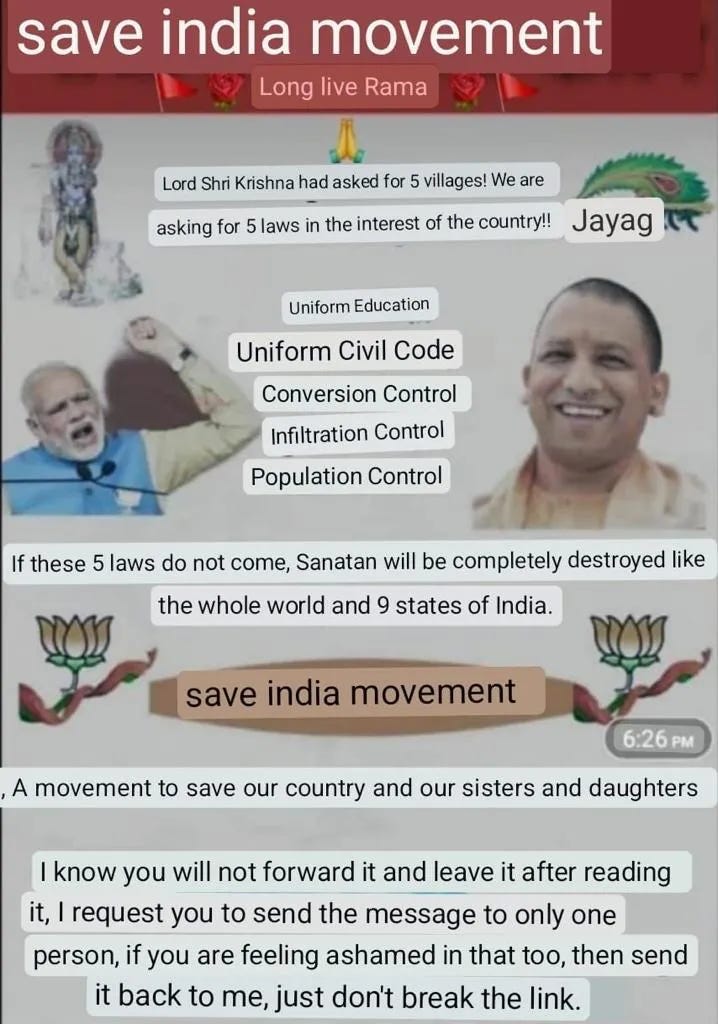

In contrast, how does one deal with the image below?

To begin with, there are no obvious ‘lies’ in the above image, which I received as a forward on WhatsApp. There are plenty of assertions and opinions in it though, and a number of assumptions.

Fact-checkers encounter images like this one all the time, and they often have no choice but to let them go. In any case, there are plenty of fact-checkable claims that keep them busy.

Why we need a ‘story-check’

Fact-checks accomplish a lot. They are a record of what is correct and what is incorrect. Fact-checks are also a product of journalistic transparency and the scientific method. At BOOM, we follow the principle of ‘show your work’ and even if readers question a fact-check, they have the option to trace the steps we took to reach the same conclusion that we did.

What fact-checks don’t necessarily do is change people’s minds1. They don’t convince those who want to believe in a particular piece of misinformation, even when offered compelling evidence not to do so.

But if facts or fact-checks can’t change people’s minds, what can?

The answer: stories. Compelling narratives that tug at our feelings can change our minds, especially if we are inundated by them. This is because human beings are hard-wired to respond to stories (which is probably why it is so easy to create propaganda and misinformation).

Logic dictates then, that in order counter misinformation, we must offer better narratives that are rooted in facts, and not in misinformation. This is actually extremely difficult to pull off, because some of the most compelling stories we are told come from our sense of history, and the histories we adopt are usually written to certain political ends.

So if we cannot offer better stories, what can we do?

A few years ago, while researching various alternatives to fight misinformation, I came to the conclusion that we must create a new form of journalistic storytelling—one that focuses on the narratives that drive misinformation. This idea isn’t without precedent, because the modern fact-check is itself a relatively recent innovation.

I decided to call this new form a ‘story-check’.

Ingredients of a story-check

To me, a story-check will need to incorporate some (or all) of the following five elements.

A fact-check as a first layer (if any of it is fact-checkable).

A ‘narrative-check’. This could be a listing of all the archetypal stories or narratives2 that a piece of misinformation might evoke.

A ‘bias-check’ — a list of all mental traps that humans are hard-wired to believe in.

An ‘emotion-check’, a list of all emotions that a piece of misinformation can generate.

A ‘context-check’, which lists coded messages in the misinformation, and answers to questions about who the message is intended for, and so on.

The example

Let’s go back to the image I shared above. What might we glean from it?

There’s a lot of going on here. When you first glance at it, your eye is drawn to the picture of Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath on the right and then to the figure of Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the left. Lord Krishna is at the top left corner, and the BJP’s symbol, the lotus, appears twice.

The phrase, ‘save India movement’ appears twice.

We then get to the heart of the message, starting with the following two lines,

“Lord Krishna had asked for 5 villages. We are asking for 5 laws in the interest of the country!!”

The ‘5 laws’ that are invoked are listed informally:

- Uniform education

- Uniform civil code

- Conversion control

- Infiltration control

- Population control.

The text at the bottom of the image states,

“I know you will not forward it and leave it after reading it, I request you to send the message to only one person, if you are ashamed in that too, then send it back to me, just don’t break the link.”

Inserted into this very crowded image is the line, “A movement to save our country and our sisters and daughters.”

1. Fact-check

There isn’t much to fact-check here. The ‘5 laws’ referred to are a cluster of laws and bits of legislation that have either

a) been made/passed,

b) are under consideration, or,

c) are the stuff of nightmares.

For example, any attempt to legislate for ‘infiltration control’ or ‘population control’ can easily be subverted, misused, or result in unintended consequences.

2. Emotion-check

The general tone of the image is one of urgency and hysteria. But in a random order, you will also find:

Panic, in the lines, “save India movement”, “sanatan will be completely destroyed'“

Passive aggression, in the line, “I know you will not forward it…”

An appeal to guilt, in the line, “if you are ashamed in that too…”

These are the emotions on the surface. But there are more subliminal appeals as well which we’ll focus on in the next sections.

3. Narrative-check

What narratives can we see embedded within the image?

This line is from the Mahabharata: “Lord Krishna had asked for 5 villages. We are asking for 5 laws in the interest of the country!!”

In the epic, the Pandavas are deprived of their right to the kingdom of Hastinapura by their cousins, the Kauravas, and are then dispatched to a 13-year exile. Upon their return, the Kauravas continue to deny them their birthright. In order to avoid a terrible war, Lord Krishna says the Pandavas will be happy even if only five villages are awarded to them. Duryodhana, the leader of the Kauravas, refuses this request.

So the two lines in the image invoke the entirety of The Mahabharata, and the narrative of good over evil. Given that the lines are placed next to the images of Yogi Adityanath and Narendra Modi, the implication is clear: the BJP is righteous and all their enemies are evil or bad.There are multiple other narratives coded into the invocation of the ‘5 laws’. Let’s tackle them one by one.

The first of these, ‘uniform education’, seems to have been tacked on as an afterthought, to fill up the ‘quota’ to make it congruent with the ‘5 villages’ theme. If it was not an afterthought, why would it be in a smaller font size and arranged diagonally?

Second, ‘uniform civil code’ refers to a set of personal laws that will apply to all citizens equally. This is a pet project of the BJP’s but comes bundled in with various contradictions. For example, with a uniform civil code in place, Muslim men will not be able to have more than one wife. But it also means that members of the LQBTQIA+ community can marry each other. The BJP has championed the former, but the government recently argued in court against same-sex marriage.

Third, ‘conversion control’ refers to another pet project of the BJP’s which is a ban on all religious conversion, with one exception: those wishing to convert to Hinduism will not be affected by these laws. (Currently 11 Indian states have conversion laws in place.)

Fourth, ‘infiltration control’ refers to the illegal movement of people across India’s borders from countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, and so on. A set of laws that have been passed focus on stopping Muslims from entering India, but the very same laws also clear the way for Hindus to do so.Fifth, ‘population control’ could be read in two different ways, as a reference to India’s explosive population, and as a veiled reference to demographic anxiety, where one community’s population (Muslim) is believed to be multiplying faster than another community’s population (Hindu).

Of course, none of these references or narratives could be understood by an outsider. Only those who live in India, or those who are familiar with India’s society, culture, and politics will get the references.

Which brings us to the next part of a Story-Check, which is a check for any other context that we’ve missed.

4. Context-check

The phrase “save our country” appears in the image, but it does not spell out “from whom?”. Given all the other religio-political messages in the image, it is pretty clear that this poster is not about protecting India from the outside world. (For example, when you gaze upon the image, you don’t think of China.)

On the other hand, the word ‘Muslim’ does not appear at all, but it is pretty evident that it is directed at the idea of ‘othering’ the community. The image exploits generic fears, anxieties and hatred of Muslims.

There is also a call to our patriarchal beliefs, because the image not only contains an appeal to “save our country” but also to “save our sisters and daughters”.

5. Bias-check

Humans are prone to dozens of mental traps, or ‘biases’ as they are known in the behavioural sciences. We fall for them because we are wired in that way by evolution. This wasn’t much a problem until the simultaneous advent of the smartphone, instant communication technologies, cheap internet and bad actors who used technology to create propaganda and polarise society to their own ends.3

Some of the biases that are operating here are:

Confirmation bias: When we look for facts to confirm our beliefs and not the other way round. For example, a person who is suspicious of the Muslim community in India, will automatically and unconsciously look for reasons that support their belief, unless they consciously choose to look past their own biases.

It is important to remember that the image above isn’t explicit. It works at the subliminal level by activating emotions that lie below the surface or on the threshold of consciousness. Such pieces of misinformation act as keys, that activate or reinforce a bunch of emotions, attitudes and feelings that have been coded into us.

In other words, the image above activates a set of feelings rather than clear ideas about Muslims in India. Taken in isolation, they are harmless, but since we can receive several such images or messages in a day, they all add up.

Authority bias: We tend to believe the opinions of authority figures we already like. In this case, the message contains an image of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. A message with his image on it, whether sanctioned by him or not, will have a greater chance of being accepted by India’s majority population.

Availability cascade: Repeat something long enough and it will become true. This explains how certain beliefs, held collectively, gain more and more credibility through repetition in the public sphere. Our information ecosystem is full of such veiled references to Muslims in India, and availability cascades explain how some erroneous beliefs become true, through constant repetition.

Bandwagon effect: We tend to believe certain things because many others believe in the same thing. In the image above, the exhortation “if these 5 laws do not come, Santan [Hinduism] will be completely destroyed…” echoes the feeling of “Hindu khatre mein hain” (Hindus are under threat).

Negativity bias: People tend to give more weightage to negative beliefs than positive ones. Here, the notes of urgency, panic and hysteria reinforce the feeling that something is very wrong with India.

I’ve noted five biases but there are many more at work here. This is just a snapshot of the kinds of biases and mental traps that are at play in the image.

And thereby ends the alpha attempt at a story-check.

Questions and what next

I won’t attempt to answer any questions that might naturally occur during this read, but I’ve anticipated some of them. Perhaps readers will have some thoughts, or perhaps some answers will percolate in later.

Is the idea of a story-check convincing? Having read this attempt, does it leave you with a sense of accomplishment or satisfaction?

Is a story-check effective and useful? Does it tell us how we fall prey to misinformation? Does it take the fact-check a step further?

How might we create a taxonomy of story-checks and a set of guidelines for them?

How do we measure the effectiveness of a story-check?

Can we train people to write story-checks? Is it sustainable, replicable, and scalable? Will a story-check work better on text or as a video?

I’ll be working on answers to these questions with the help of various colleagues and collaborators. If you’re interested in working with us, do write in to hrv@boomlive.in with the subject line: story-checks.

This assertion is not entirely accurate. There is evidence that fact-checks do in fact change people’s minds, but only under certain circumstances.

Can all the narratives or stories of the world be boiled down to certain archetypes? Christopher Booker, in his 2004 book, The Seven Basic Plots, made an attempt to do. His schema has takers and critiques.

My colleague Archis Chowdhury adds a more nuanced take on this note. He says, “biases have always been a root cause of major social upheaval, including a millennium of anti-semitism ending with the holocaust, along with many other ingroup-outgroup examples of aggression around the world, including the spread of pseudo-scientific beliefs that defend racist ideas during the times of slavery.”