Praja Dharma In The Age Of Modi 3.0

6 stories of dissent, inquiry and accountability from India's scriptures, literature and folk traditions.

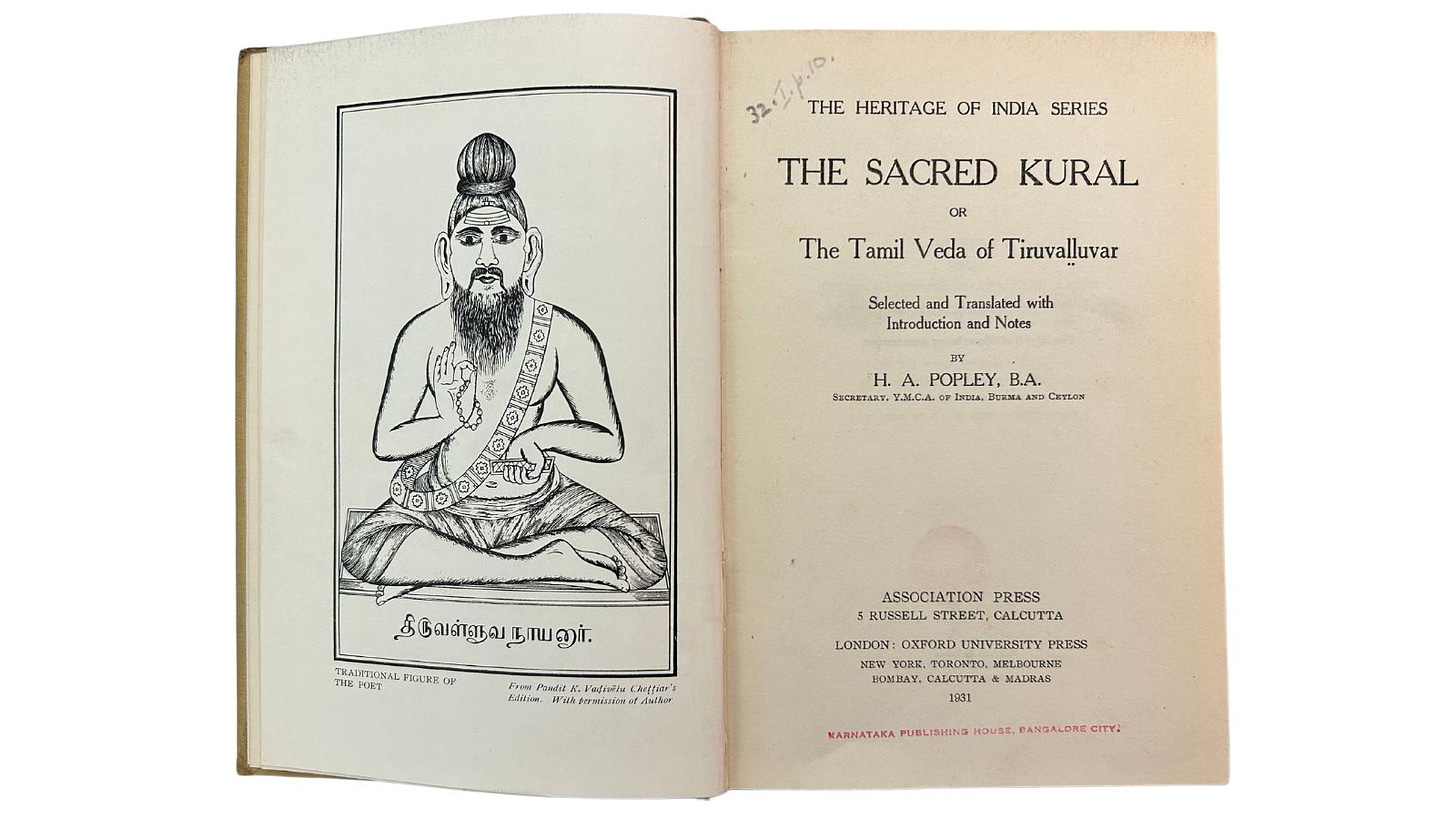

“If the king is a stingy fatpurse or grinning bag of bluff”, says Tiruvalluvar, “he commands no more respect than a stuffed sack of fluff.”

This couplet, in a delightful translation by Gopalkrishna Gandhi, is from the Tirukkural, an ancient1 collection of wisdom written in Tamil by the aforementioned Tiruvalluvar. The wisdom contained within the kural is divided into three sections or ‘books’, and this couplet is from the middle one titled porul, which relates to government, society and politics.

Now that we have had a new government sworn in (with the same prime minister, albeit cut down to size), are we all going to go back to the way it was during Modi 1.0 and 2.0? You know, when most people (except for a courageous few) did not question him or his government, or demand accountability? When the movement to silence the people was led by TV news?

We now have an opportunity to reset and recalibrate our understanding of what it means to be citizens, and to speak truth to power as journalists.

I thought that one way to do that would be to take a palm-leaf out of the Hindu right’s playbook, and look at India’s parampara (tradition), pratishtha (prestige) and anushaasan (obedience) for inspiration.

It turns out that there are plenty of examples of speaking truth to power in India’s history, literature, and cultural and folk traditions. Here are six of them. A quick note: ‘Praja Dharma’ literally means the ‘virtuous path of the citizen.’

1. Spirit of inquiry and wonderment in the Nasadiya Sukta of the Rig Veda

One can scarcely question anything in India without the spectre of ‘hurt sentiments’ arising. But the people who take offence at the smallest thing should be told all about the spirit of inquiry and wonderment in the Rig Veda.

Seven verses in the Nasadiya Sukta (नासदीय सूक्त), found in the 129th sukta (सूक्त)of the 10th mandala of the Rig Veda (ऋग्वेद) demonstrate that the spirit of free-flowing inquiry is baked into the Hindu way of thinking.

Here’s the sixth verse.

को अ॒द्धा वे॑द॒ क इ॒ह प्र वो॑च॒त्कुत॒ आजा॑ता॒ कुत॑ इ॒यं विसृ॑ष्टिः ।

अ॒र्वाग्दे॒वा अ॒स्य वि॒सर्ज॑ने॒नाथा॒ को वे॑द॒ यत॑ आब॒भूव॑ ॥ ६॥ Translation:

But, after all, who knows, and who can say

Whence it all came, and how creation happened?

The gods themselves are later than creation,

Here’s the seventh verse.

इ॒यं विसृ॑ष्टि॒र्यत॑ आब॒भूव॒ यदि॑ वा द॒धे यदि॑ वा॒ न ।

यो अ॒स्याध्य॑क्षः पर॒मे व्यो॑म॒न्सो अ॒ङ्ग वे॑द॒ यदि॑ वा॒ न वेद॑ ॥ ७॥Translation:

Whence all creation had its origin,

he, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not,

he, who surveys it all from highest heaven,

he knows - or maybe even he does not know.

These hymns have been translated multiple times and have seen frequent debate, and it is clear that there is a spirit of enquiry at the heart of the Nasadiya Sukta. There is existential enquiry, mystery, uncertainty, and the final verse introduces the idea that perhaps even the supreme creator may not know the origin of creation.

Sounds radical, no?

But it isn’t. Not really. This unique form of skepticism, coming right from the very DNA of Hindu philosophy has largely been forgotten today. But it is there for us to rediscover.

Next time you feel like you don’t have the right to question power, think back to the Nasadiya Sukta, and its spirit of inquiry and intellectual humility. Think of its tolerance to ambiguity.

On Reddit, I came across a post that said that the questions posed in the Nasadiya Sukta are answered later on in the Rig Veda. I’m no expert, but because the verses of the Nasadiya Sukta form a self-contained unit, the point still stands.

2. Even Dharma has Karma (or how gods too are accountable)

Kings, ministers, and even gods are held accountable in various Indian traditions.

To illustrate that, let me narrate the story of how Lord Dharma himself was punished for foregoing dharma. It’s an appropriate choice for this post, because it shows that even the mighty Dharma, more commonly known as Lord Yama, the god of death, was punished for failing his dharmic duty.

Here’s the story in my own telling, with some modern flourishes. (There are slightly different versions and you can find them many of them online.)

Once upon a time there was a powerful sage named Mandavya who lived by himself in his ashram in the forest. Once, while deep in meditation, he did not notice a band of robbers rushing in to hide in his abode.

Now these robbers weren’t exactly playing hide and seek. They were in fact running from the king’s Z-plus security team, having plundered the royal treasury.

When the king’s guards burst upon the scene, they assumed Mandavya was one of the robbers. Then, following all procedures as per the shastras (aka after reading him and the others their rights), they arrested them.

The king was so enraged that he gave them the standard punishment of death through impalement. Pierced by sharp stakes that were affixed to the ground, they all died one by one. Except for Mandavya, who had tremendous yogic powers and continued to breathe despite being in utter agony.

When the king realised who the great sage was, he had Mandavya cut down from the stake. He begged for forgiveness and patched him up as best as he could. Despite the best efforts of his expert team of healers, the stake could not be removed entirely. From now on, the sage would have to go about his daily business with the stake still inside him.

Mandavya wanted justice. But he chose to forgive the king who was after all a mortal. Instead, he used his formidable powers of meditation to reach the heavenly abode of Dharma. He asked the god why he had to undergo such a gruesome ordeal.

Whereupon Dharma replied that as a child, Mandavya had struck blades of grass upon the tails of insects, thus impaling them. “Your ordeal was the consequence of such an act”, said Dharma.

Mandavya then asked, “how old was I when I committed these acts?”

Dharma said, “10 years old.”

Mandavya then said, “you forgot that a sin committed by a 10-year-old should not be considered a sin.”

He then cursed the god to lose his immortality and be born as a mortal. Not just that, the condition of the curse was that Dharma could not exist as a god so long as he lived his mortal life2.

There are other versions3 of this story. In one of them, Mandavya says the punishment was too large to fit the crime, and therefore changed the dharmic rule. But just like with the Nasadiya Sukta, the point stands.

In other words, even Dharma has karma.

Indian philosophy shows that no one is above accountability, neither a god, nor a king not for that matter a prime minister and his band of ministers!

3. How Tenali Raman challenged the goddess

We’ve seen two examples from India’s sacred texts. However, folk traditions and stories are a rich source of inspiration about dissent as well.

The stories of Tenali Raman and how he put the mighty Tuluva king Krishnadevaraya in his place are legion. Here’s the story of how he got his start.4

In a South Indian village called Tenali there lived a clever boy. His name was Rama. Once, a wandering sannyasi was impressed with the boy's looks and clever ways. So he taught him a chant and told him, “If you go to the goddess Kali's temple one night and recite these words three million times, she will appear before you with all her thousand faces and give you what you ask for—if you don't let her scare you.”

Rama waited for an auspicious day, went to the Kali temple outside his village, and did as he was told. As he finished his three-millionth chant, the goddess did appear before him with her thousand faces and two hands. When the boy looked at her horrific appearance, he wasn't frightened. He fell into a fit of laughter.

No one had ever dared to laugh in the presence of this fearsome goddess. Offended, she asked him, “You little scalawag, why are you laughing at me?”

He answered, “O Mother, we mortals have enough trouble wiping our noses when we catch a cold, though we have two hands and only one nose. If you, with your thousand faces, should catch a cold, how would you manage with just two hands for all those thousand runny noses?”

The goddess was furious. She said, “Because you laughed at me, you'll make a living only by laughter. You'll be a vikatakavi, a jester.”

“Oh, a vi-ka-ta-ka-vi! That's terrific! It's a palindrome. It reads vi-ka-ta-ka-vi whether you read it from right to left or from left to right,” replied Rama. The goddess was pleased by Rama's cleverness that saw a joke even in a curse. She at once relented and said, “You'll still be a vikatakavi, but to a king.” And she vanished.

Soon after that, Tenali Rama began to make a living as jester to the king of Vijayanagara.

4. Birbal’s dissent against Akbar

If Tenali Raman is near, can Birbal be far? Just like the stories circulated about the emperor of the Chalukyas and his jester, there are stories about Birbal and the emperor Akbar of the Mughals. Here’s one.

Sons-in-Law

One day, when Akbar and Birbal were out hunting, the emperor pointed to a crooked tree and said, 'Why is that tree crooked?'

Birbal answered, 'That tree is crooked because it is the son-in-law of all the trees in the forest.'

"Why do you say that?" asked Akbar.

Birbal quoted a proverb: 'A dog's tail and a son-in-lav are always crooked.'

Akbar asked, 'Is your son-in-law also crooked?

"Of course, Your Majesty!' said Birbal.

“Then have him crucified," said the emperor.

A few days later, Birbal had three crosses made. When Akbar saw them, he asked, ‘Why have you made three crosses?'

Birtal answered, ‘Your Majesty, one of them is for you, one is for me and one is for my son-in-law.'

'And why are we to be executed?' asked Akbar.

"Because,' said Birbal, "we are all the sons-in-law of someone."

Akbar laughed and said, “let your son-in-law go!”

5. A Minister’s Duties in the ‘Tamil Veda’ of Tiruvalluvar

We’ve already seen a couplet from the Tirukkural in the beginning. But it’s worth spending more time with it, particularly Book II, which functions as a handbook for princes and kings.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi says that Book II is a compilation of “very friendly advice to the occupier of the throne. The advice is: be wise, politic, smart, do not squander the opportunity to be a good warrior, a wise administrator, a protector of the kingdom’s material and human wealth.”

In Book II, one can find many passages of good advice.

Here’s another couplet from Chapter 44:

That king is king who’ll first his own faults own

And only then those of others bemoan

In other words, a good leader must have the capacity to be reflective.

What stood out for me, however, was the Tirukkural’s verses on what makes a good minister to a king. The advice is quite relevant for our ministers.

Here it is, in full.

Chapter 64

The Good Minister

631

Resources, a sense of time, right ways to oversee

Make the minister what a minister should be

632

Bold, un-relaxed in vigil, learned, wise

Being these makes a minister to his full scope rise

633

The minister who can split his foes, win angered friends back

And hold them, has that gift called 'knack'

634

The minister with sharp eyes sees

What will work, what won't

And, pondering them with calm, decrees:

'Do this like this and as for that—just don't'

635

The minister who knows what's right and says it right

Aids the kingdom by his inner and 'over' sight

636

No problem's too big for a minister whose genius

'Native' as it's called, aided by the codes, is there to serve us

637

The minister who has mastered the manipulator's tract

Must yet find out how nature makes men act

638

The minister must from his seat say loud and ringing-clear

What he must, though a haughty king, and unwise, may refuse to hear

639

The minister who intrigues under the monarch's very nose

Beats by far, by very far, his seventy crores of foes

640

The minister who relies on plans and lofty schemes alone

But forgets the ground stumbles on reality's stoneCan we have some ministers like that please?

6. A thinking tool for citizens… from an old joke

These examples above demonstrate the spirit of inquiry, accountability and dissent. I hope they are inspirational. Let’s now see if an old joke can be utilised as a tool for thinking:

One dark night an old woman was searching intently for something in the street. A passer-by asked her, 'Have you lost something?' She answered, 'Yes, I've lost my keys. I've been looking for them all evening.' "Where did you lose them?" "I don't know. Maybe inside the house.' "Then why are you looking for them here?' 'Because it's dark in there. I don't have oil in my lamps. I can see much better here under the streetlights.'

The joke is from the introduction to Folk Tales From India, compiled and edited by A. K. Ramanujan. As the title makes clear, it is not a compilation of jokes. However, Ramanujan tells it to make a point:

“Until recently many studies of Indian civilization have been conducted on that principle: look for it under the light, in Sanskrit, in written texts, in what we think are well-lit public spaces of the culture, in places we already know.

There we have, of course, found precious things.

Without carrying the parable too far, in a book like this, we may say we are now moving indoors, into the expressive culture of the household, to look for our keys.

As it often happens, we may not find the keys we are looking for and may have to make new ones, but we will find all sorts of other things we never knew we had lost, or ever even had.”I think we can stretch Ramanujan’s analogy a little bit to suit our purposes.

In our efforts to speak ‘truth to power’ (in the case of the opposition) and in the our efforts to support the Modi government at all costs (in the case of the Hindu right), are we ‘looking under the streetlights’? What will happen if we go ‘back indoors’?

That is, what will happen if we look within ourselves? Will the Hindu right find good reasons to demand accountability of the Modi government? Will the liberals find other ways to dissent, perhaps like Tenali Raman and Birbal, from within?

The questions are many.

Ramanujan says that when we move indoors to look for the lost keys, we might also have to ‘make new ones’. The process of ‘making new keys’ can be seen in two ways:

New tools to be good citizens, whether it is by holding ‘praja sabhas’ (for every one) or by creating digital tools for investigations (for journalists).

New ‘thinking tools’ and frameworks.

This post has been an attempt to reframe the idea of dissent for the majoritarian Hindu. Even though it deploys old traditions, in this context, it is a new ‘thinking tool’.

To repeat myself, we are now at a new crossroads in our journey as citizens. We can reset and recalibrate.

In order to write this piece, I took a slow and meandering walk through India’s literature, culture and folklore. My conclusion is that we can make this list a lot bigger. What’s missing from this list are examples from the Buddhist tradition (Jataka Tales), subcontinental Islamic lore (Mullah Nasruddin or Naseeruddin Hodjra), early Christian myths and so on.

I also read through The Panchatantra and a little bit of Baital Pacheesi (Vikram Betal) for cautionary tales, but could not find anything explicitly about dissent and accountability.

What other stories, traditions, scriptures came to mind while reading this piece? Write back to me or here with your ideas!

Disclaimers and Corrections:

When one mines India’s traditions and literature for material, one encounters caste and gender-related conundrums. Historical texts have limitations, but I don’t think it is a good idea to ignore them. For now, I sidestepped that question by removing all references to caste, particularly from the stories of Tenali Raman and Sage Mandavya.

In an earlier version of this piece, I referred to Krishnadevaraya as a Chalukya king. He is actually a Tuluva king. The error is regretted.

How old is the Tirukkural? It depends on how you approach its dating, but it’s believed to be from a broad range spanning 600 years, from the first century BCE (BC) to the sixth century CE (AD). The translation I’m relying upon is by Gopalkrishna Gandhi published in 2015.

As divine fulfilment of the curse, Mandavya was reborn as Vidura, the wisest human of all.

I cross-referenced the story from two sources: The Hindus, An Alternative History by Wendy Denier and from the online writings of Aniket S Sharma.

This story is taken from the collection Folk Tales From India, compiled by A K Ramanujan.

I think Krishnadevaraya was a king of the Tuluva dynastry of Vijayanagara empire.

This is a very pertinently timed piece, and an excellent curation of examples from the traditions purportedly upheld by the Hindu right.

If only they’d bother to read!